7 Chapter 6: “Nature, Embodied: Performance, Resistance, and Environmental Justice” by Alex Davenport

Introduction

This chapter seeks to find areas of connection between two different subdisciplines—environmental justice and performance studies—by centering on the question and idea of resistance. What does it mean to resist? To open up space for resistance? What counts as resistance and who gets to decide? This chapter does not answer these questions but, rather, offers examples to illustrate a space where you can explore them yourself. To do this, I first provide an overview of environmental justice and performance studies: think of this as the background of the landscape we are about to explore, a suggestion of its horizons. I then use a three-pronged approach to performance to offer examples of spaces that performance and environmental justice overlap. These are various, related species that populate the landscape we explore: all related by the questions of resistance but evolving differently to respond to different challenges and needs. Finally, we zoom out, suggesting the landscape beyond the horizons illuminated in this chapter.

Reviewing the Landscape

To provide an exhaustive review of the work and research that has occurred in environmental justice, performance studies, or even in the spaces of overlap between the two is beyond the scope of this chapter; so, I invite you to encounter this as a snapshot: a glimpse of a scene captured on a photograph that has been sent to you by another traveler, with their own investments, interests, aesthetics, and values. I do so because this is a principle that most scholars and practitioners within the fields of environmental justice and performance studies find important: the subjectivity of the individual. You may already be familiar with this principle through standpoint theory. Originally articulated as such in the 1970s and 1980s, standpoint theory asserts that groups and individuals come to know and experience the world in ways that are shaped by their particular socio-political positions (Harding, 1986; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). While standpoint theory, in and of itself, is concerned with highlighting the perspectives of marginalized peoples it also points to the fact that “objectivity” as it is commonly understood is a myth that is also grounded in a particular position and way of viewing the world. As such I invite you to question what you encounter here, to challenge it, to explore it further, open to new discoveries and nuance.

Environmental Justice

While there is definite overlap between the environmental movement—which is “dedicated to environmental integrity and preservation” (Pezzullo & Sandler, 2007, p. 1)—and the environmental justice movement—which is “dedicated to justice in the distribution of environmental goods and decision making” (Pezzullo & Sandler, 2007, p. 1)—it is also important to recognize that they are not one and the same. While the end goals may be similar, this is not, necessarily, the case. In their introduction overviewing environmentalism and environmental justice, Pezzullo and Sandler (2007) acknowledge the ongoing criticisms the environmental justice movement has levied against the mainstream environmental movement: an agenda that is focused on the “natural world” without a consideration of individuals that is often impacted by racism, classism, ableism, and more (p. 2). This is reflected in the initial articulation of the environmental justice movement as one that considers the environment to be composed of those areas where we “live, work, and play” (Alston, 1991, p. 103). Because of the necessity that people be considered as a starting point for environmental justice, this helps to form a strong connection to the practices of performance studies, which is discussed below.

Performance Studies

Pelias and Shaffer (2007) trace performance studies—a subdiscipline in communication studies—back to the practice of oral interpretation of literature (p. 15). Extrapolating from this, we can understand performance studies as a discipline concerned with re/making meaning through the embodied process of interpretation of cultural texts (Schechner, 2013). This interpretation can range from aesthetic interpretation—often found in what is called conspicuous performance, usually seen in the arts—to everyday interpretation—seen in our interpretation of what it means to belong to a specific social group like our gender or race. Before moving on it is worth offering a quick note regarding this latter end of the interpretation spectrum. From a performance studies lens, just because something is a performance (e.g. race, gender, sexuality, etc.) this does not mean that it does not have real socio-political and personal effects; rather it is a performance in that identities—in the social-scientific sense—are formed by processes of reiteration, citation, and practice (Butler, 1993, p. xii).

A helpful framework is also offered by my colleague, Dr. Colin Whitworth in their performance Bless our Hearts “[performance studies] uses performance in three primary ways….The first way is we use performance as a way to represent our research….The second way we use performance is as a way to theorize….And the third way we use performance is as something to write about or critique” While these uses do not exist in isolation (research may be staged, which then is critiqued, restaged, theorized, and so on), thinking about them in this way to start offers a good heuristic.

A Selection of Species

For the purposes of this chapter, I am going to present three examples of intersections between environmental justice and performance that, also, follow three approaches to performance. First, I will introduce an example of conspicuous performance. Then I will introduce an example of performance within daily life, highlighting both how the framework of performance can be used to understand these instances along with the ways that they exist as conscious acts of performance. Finally, I will introduce what is probably the least familiar intersection/approach: performative writing. We will discuss what performative writing is, before working through an example.

Conspicuous Performance

The stage lights go up, a soundstage with a mix of forest sounds and voice-over begins to play as the performer enters in hiking gear. Carrying a hiking stick he circles around the stage, stopping at and returning to a circle of rocks reminiscent of a fire-pit, a wooden park bench, the sides and lip of the stage. Throughout this process music begins to layer into the sounds before the performer reaches the edge of the stage, looks out to the audience as if observing a vista while hiking, and the sound goes silent. We hear them say, finally, “Nice… Heck of a view, eh? Best I’ve seen so far. Yeah, I’ve been on this trail for three days now. When we started out, my friends promised me that by now it would be oh so easy. ‘Magic of the trail’ and all that. Yeah, right! This pack is killing me! Every day, a ten-mile hike or so—up and down, up and down. My knees are SCREAMING!!!!” (Gray, 2010, p. 201). These are the opening moments of Dr. Jonathan Gray’s Trail Mix.

Throughout the performance we are guided by the narrator and meet two other personas, the bear—a play on both the animal and the slang for a larger gay man—and the tree sitter—inspired by many activists, but notably Julia Butterfly Hill—however I wish to focus on the figure of the bear.

This section marks the performer as queer, as they engage with the socio-cultural overlap of understanding: the bear (nonhuman animal) as a danger to humans, the bear (human) as lecherous and predatory; the bear (nonhuman animal) as under threat from human hunting and destruction of habitat, the bear (human) as under threat from legislation and homophobia. As Craig Gingrich-Philbrook recounts, at one performance of Trail Mix, done for Earth Day in a local park, this particular section was met with little boys throwing rocks at Gray (Gingrich-Philbrook, 2010). The performance itself takes on issues of environmental justice; but this reaction highlights the question of which non/human subjects are deemed worthy of accessing and existing within public space and under what conditions.

The overlap between advocacy and/or environmental communication and performance practices is, perhaps, one of the easier to understand. After all (most) conspicuous performance has some sort of textual element to it. The challenge, then, becomes one of translation: how do the myriad of rhetorical tools present in performance practice—embodiment, staging, props, the script—translate issues, experience, research, and more; and to what audience? It is precisely because conspicuous performance has tools that escape the written word that a queer performer taking on the persona of a campy, referentially queer bear is able to illustrate connections in a way that is accessible and known within and through the body. Importantly, though, conspicuous performance will almost always emerge from a process: scripting, rehearsals, blocking, and so on create a performance that can, with little variation, be repeated in a variety of different venues. Everyday performance, which we turn to next, is also rehearsed, although not in the same ways or for the same purpose.

Everyday Performance

In their groundbreaking article “Beyond Persuasion,” Sonja Foss and Cindy Griffin (1995) offer a vision of invitational rhetoric: “an invitation to understanding as a means to create a relationship rooted in equality, immanent value, and self-determination” (p. 5). To give further context to this they draw on an example of activism recounted by Starhawk (1989). In this instance, activists have been arrested for protesting the construction of a nuclear power plant and are being held in a school gym. One woman, in trying to escape violence from those guarding them, dives into the group. During the ensuing struggle, “one woman sat down and began to chant. As the other women followed suit, the guards’ actions changed in response” (Foss & Griffin, 1995, p. 10).

On one hand, we could easily describe this event in terms of performance. Drawing on Kenneth Burke’s pentad (Burke, 1969) reveals language that is so embedded we may not think of it, automatically, in terms of performance. What happened (the act)? When and where did it occur (the scene)? Who was involved (the agent)? How did it occur (agency)? Why did it happen (purpose)? The journalistic questions are, already, steeped in the language of performance because it provides a way for us to readily understand and orient to an event, we are—after all—a people of stories (Fisher, 1984).

But this is also an act of conscious, though perhaps not conspicuous, performance. The activists who were arrested initially formed a blockade, drawing on long standing activist strategies and images. In sitting down to chant, they draw on familiar activist activities (the protest song) while also embodying activist strategy (it is hard to claim someone resisted arrest simply by sitting and singing) and pointing towards common activist principles (nonviolent resistance). Here, while the activists probably had a variety of trainings to help prepare for different protest scenarios, they are not drawing on the same process of rehearsal and scripting that leads to a conspicuous performance; rather, like gender, “the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects that it names” (Butler, 2010, p. xii). That is to say that the practice was understandable as civil disobedience because of the wider vocabulary of tactics and strategies that were being drawn upon, even if it was improvisational in its execution.

While both conspicuous performance and everyday performance, for our purposes, have explicitly fore fronted the body, performance studies does not necessarily limit the body to a self-evident aspect of performance; which is highlighted in the final strategy we discuss below.

Performative Writing

Earlier I noted that performance studies focused on embodiment, and so it may seem counterintuitive to turn, now, toward writing; however, as Dr. Tami Spry (2011) notes, the text and the body are inexorably linked (p. 20). Writing, then, is also an embodied practice: it flows from, engages, and transforms the body. Performative writing, specifically, performs itself; existing in continuous relationship with theory/writing/performance (Madison, 1999) it does something and encourages the reader to see mysteries (Goodall, 1991; Pelias, 2005, p. 417) rather than objective, or even subjective, fact. Performative writing seeks “to recall performative writing to performance” (Pollock, 1998, p. 74).

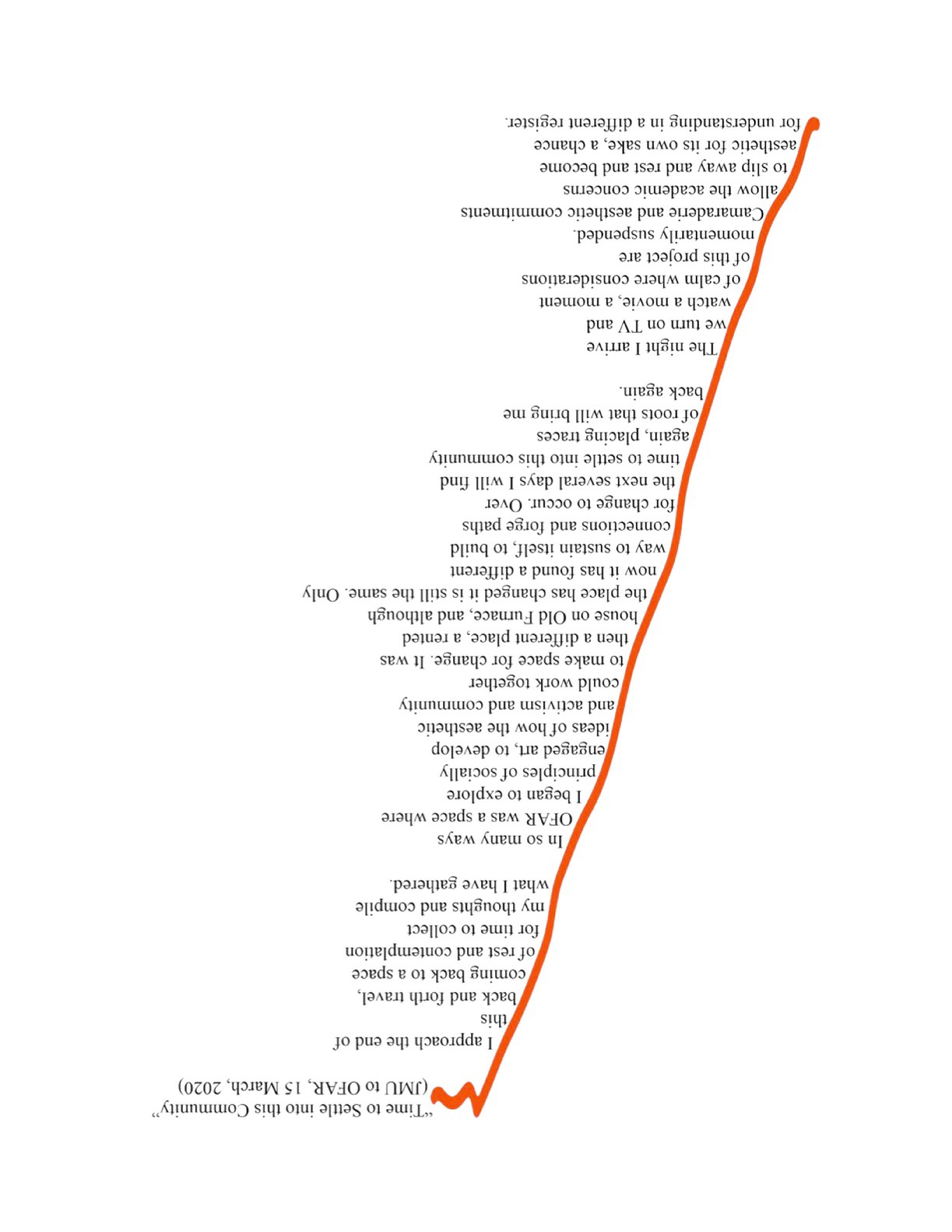

To provide an example of this, I turn to an example from my own work. The project that this excerpt is taken from was centered on the creation and touring of a memorial quilt for anti-mountaintop removal activist Julia “Judy” Bonds, who died in 2011. Many people knew Bonds through her speaking engagements, and part of the project involved traveling to sites she spoke at to deliver a performance lecture about her work, legacy, and the ongoing community organizing in Appalachian communities. To reflect on this travel while also engaging the reader through performative writing practices, I drew on principles of poetic inquiry (Faulkner, 2016) and the use of experimental typographic configurations to highlight affective and linguistic meaning simultaneously (Coupland, 2006; Eggers, 2003; Sterne, 2003). The poetry recounting my travel used line breaks to emphasize rhythm, was situated alongside a visual representation of the routes I traveled, and oriented to suggest the main direction of the travel that occurred during that portion of travel (i.e. top to bottom for North to South, left to right for East to West, bottom to top for South to North, and right to left for West to East).

Time to Settle into this Community (Alex Davenport, 2023). Permission given by author.

Performative writing, in this case, substitutes the performer’s body with the body of the reader, placing them into the experience of orienting to a textual type of travel. Because this is the last poem in the chapter, the reader has gone through a process of dis/re-orientation, with seeds of environmental justice issues and citations placed throughout. Like conspicuous performance, performative writing has the potential to play with traditional modes of advocacy and make it accessible in a different way. However, the writer also must contend with questions that are not present in more traditional forms of research: how do I align the form and function of the piece, how far can I push the reader, and—importantly—what skills do I need to develop to ensure this?

Conclusion: A Panoramic View

This chapter has sought to illustrate potential areas of overlap between environmental justice and performance practice; but it should not be assumed these are the boundaries of this landscape. From the work of The Composters (Donoghue & Fisher, 2008) to that of toxic tourism (Pezzullo, 2003), performance, resistance, and environmental justice overlap in numerous ways through numerous strategies. At the end, though, they are marked by an insistence that the body and community be centered in the conversation, that affective and deliberative knowledge both have a role to play: a part of, rather than separate from, the environment.

References

Alston, D. (1991). Moving beyond barriers. National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, Washington, D.C.

Burke, K. (1969). A grammar of motives. University of California Press.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. Routledge Classics.

Butler, J. (2010). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Coupland, D. (2006). JPod. Bloomsbury.

Davenport, A. (2023). Threading memory: Performing animacy in text, memorial, and travel [Dissertation, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale]. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/2097/

Donoghue, J., & Fisher, A. (2008, 2008/07/01). Activism via humus: The Composters decode decomponomics. Environmental Communication, 2(2), 229-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030802141778

Eggers, D. (2003). You shall know our velocity! Vintage Books.

Faulkner, S. L. (2016). Poetry as method: Reporting research through verse. Routledge.

Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51(April), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180

Foss, S. K., & Griffin, C. L. (1995). Beyond persuasion: A proposal for an invitational rhetoric. 62, 2-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759509376345

Gingrich-Philbrook, C. (2010). I love this animal. Text and Performance Quarterly, 30(2), 222–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930903244745

Goodall, H. L., Jr. (1991). Living in the rock n roll mystery: Reading context, self, and others as clues. Southern Illinois University Press.

Gray, J. (2010). Trail mix: A sojourn on the muddy divide between nature and culture. Text and Performance Quarterly, 30(2), 201-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930903245064

Harding, S. (1986). The science question in feminism. Cornell University Press.

Hill Collins, P., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press.

Madison, D. S. (1999, 1999/04/01). Performing theory/Embodied writing. Text and Performance Quarterly, 19(2), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462939909366254

Pelias, R. J. (2005). Performative writing as scholarship: An apology, an argument, an anecdote. Cultural Studies <—> Critical Methodologies, 5(4), 415-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708605279694

Pelias, R. J., & Shaffer, T. S. (2007). Performance studies: The interpretation of aesthetic texts (2nd ed.). Kendall/Hunt.

Pezzullo, P. C. (2003). Touring “Cancer Alley,” Louisiana: Performances of community and memory for environmental justice. Text and Performance Quarterly, 23(3), 226-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930310001635295

Pezzullo, P. C., & Sandler, R. (2007). Revisiting the environmental justice challenge to environmentalism. In R. Sandler & P. C. Pezzullo (Eds.), Environmental justice and environmentalism: The social justice challenge to the environmental movements (pp. 1–24). The MIT Press.

Pollock, D. (1998). Performing writing. In P. Phelan & J. Lane (Eds.), The ends of performance (pp. 73–103). New York University Press.

Schechner, R. (2013). Performance studies: An introduction (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Spry, T. (2011). Body, paper, stage: Writing and performing autoethnography. Routledge.

Starhawk. (1989). Truth or dare: Encounters with power, authority, and mystery. HarperOne. (1987)

Sterne, L. (2003). The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Penguin Classics.