1 Introduction

How Introducing Environmental Justice Advocacy Came to Be

At the start of the fall 2024 semester, our graduate seminar on environmental justice (SCOM 652: Environmental Justice: Advocacy and Perspectives) at James Madison University, as part of our MA program in Communication and Advocacy, had far fewer students enrolled than in each of the previous iterations of the course (in particular, two students enrolled this semester). It was important to me (Matt) that the experience of this seminar by Doreen and Grace would not feel like it was working off of a deficit model–things we were unable to do because of the small seminar size–but instead treating this space as an inventive opportunity to do something that could not be done by a larger seminar and thus was only possible because of our small group.

The next step in our process was to determine a kind of signature/defining focus for our work this semester. We considered devoting this semester to enabling co-editors Doreen and Grace to submit a scholarly manuscript to a conference/journal and hopefully eventually be published. However, since both of these graduate students are already learning about that kind of work, with other projects that they have written while in the graduate program, we instead looked elsewhere.

Over the last several years, in large part due to concerns about the ever-growing costs of textbooks at colleges and universities, a movement to build OER (Open Educational Resources) resources that could serve as free alternatives to traditional textbooks has gained significant momentum (Mickel & Scida, 2023).[1] Though it is a lot to hope for in just one semester, we thought (especially since the JMU Libraries has a fantastic team member, Liz Thompson, an Associate Professor and Open Education Librarian, with expertise in and focused full-time on OER work), let’s give it a try, but rather than having the three of us try to write most/all of it, we would invite those in the program who have (for their seminar papers, theses, and/or work since then, such as conference papers, publications, or dissertations) done work that relates to environmental justice to contribute to the OER textbook you now have in front of you: Introducing Environmental Justice Advocacy. The timing seemed fitting, since this is the 10th anniversary of our graduate program, and thus both due to their excellence and background in Environmental Justice, we would reach out to them about contributing a chapter (approximately 2,000-2,500 words total for each contributed chapter).[2] We reached out to 18 alumni, each of whom met three criteria: 1) they completed our graduate program and concentrated in the environmental concentration; 2) they completed one of the previous iterations of this SCOM 652: Environmental Justice graduate seminar; and 3) we felt like work that they had done either during the program or since could usefully contribute to the OER textbook, providing a resource that faculty could use to assist in teaching environmental justice in upper-level undergraduate classes (those at the 300//400-level) and in graduate seminars for those newer to graduate studies (such as in a master’s program).

We proposed an initial topic idea for each person when we invited them, and then we worked with them to fine-tune and finalize their chapter topic. Contributors submitted preliminary drafts of the chapter, and the three of us deliberated on and wrote one combined review letter for each drafted chapter that provided a decision and a set of necessary edits. We did not aim to create anonymous peer review, and we also were not attempting to produce a certain acceptance/rejection rate (in our eyes, ideally, if everyone completed all of the requested revisions, we would be able to include all of the submissions).

What is Environmental Justice?

We quote here at length from Phaedra C. Pezzullo and Robert Cox’s Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere, since theirs is one of the most-utilized textbooks about environmental communication and rhetoric, and though the book is not solely or even mostly about environmental justice, their description of what it is and why it emerged is particularly helpful as a way of approaching our textbook:

As used by community activists and scholars studying the movement, environmental justice refers to (a) calls to recognize and halt the disproportionate burdens imposed on working-class and people of color communities by environmentally harmful conditions, (b) more inclusive opportunities for those who are most affected to be heard in the decisions affecting their communities, and (c) a vision of environmentally healthy, economically sustainable, and culturally thriving communities. … This grassroots movement redefined environment to encompass where we live, work, play, and learn–and some add where we pray to include, for example, indigenous sacred sites and Appalachian graveyards. Although this movement now emphasizes urban gardens and green spaces, it began out of a broader, emerging critique of toxic pollution patterns and the marginalization of voices.[3] (Pezzullo & Cox, 2018, p. 258)

Like many ideas of its kind, environmental justice (and environmental justice activists) do not recognize only one definition as correct. Indeed, in the contributions that are included in this book, you will see many occasions when an author supplements or supplants the definitional ideas provided above. We encourage you to take in and consider these various definitions/aspects, and ultimately as you complete this area of study you will hopefully have, with some borrowing and synthesizing, developed your own definition of environmental justice!

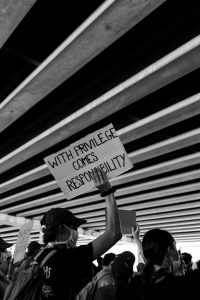

grayscale photo of woman holding sign. Lan Johnson. https://unsplash.com/photos/grayscale-photo-of-woman-holding-sign-aHlZv23P8YQ. Free to use under the Unsplash License.

Advocacy and the Is/Ought (Descriptive/Normative) Dilemma in Environmental Scholarship

As noted above, each of the authors featured in this OER book a) has undertaken graduate coursework in environmental justice and b) has done so as part of a larger graduate program centered on “communication and advocacy,” wherein they concentrated in the area of environmental communication. We often have students in the program strongly committed by the ethical impulse to confront the environmental crisis “before it is too late”: “It is late. We are deep in an emergency. But it is not too late, because the emergency is not over. The outcome is not decided” (Solnit, 2023, p. 3). Those who care deeply about these issues wrestle with the ongoing question of whether environmental communication is or should be a “crisis discipline” (Cox, 2007). Doing so might commit its community to the need for “taking sides,” especially in moments that seem dire. The question of whether there is a normative sensibility at the heart of this scholarly community is but one of many questions for would-be advocates (or even “activists”). We offer in this volume seven contributions, each of which offers its own take on whether environmental justice advocacy involves an “ought,” and if so, how one determines what that action might be. Thus, rather than asking you to adopt the stance that any or all of us, as editors and authors, might take, we ask instead that you consider which of these claims best resonates with your own outlook (knowing that outlook likely will change over time).

How this Work Fits in the Larger Landscape of Published Environmental Justice Material

There are now an abundance of works, including scholarly peer-reviewed ones, in terms of articles, book chapters, and full-length books. The role of our book points in two slightly different directions: 1) as an open resource, this book shortcuts the challenges of asking students (and sometimes teachers/faculty) to pick up the cost of such material, and 2) given the maturation and growth of environmental justice as a kind of inquiry, we felt comfortable giving contributors wide range over what they wanted to focus on in their chapters, with the idea being other works have already done the kind of surveying/mapping out of the full field in a comprehensive way, and thus that this book could offer specific readings and perspective that might direct the faculty and students in an unanticipated yet important direction.

Finally, we want to suggest that readers whose concern is more about working through the vexing of how to teach about environmental justice, focused specifically on issues of pedagogy, there is other work that can be helpful in this regard. Most notably, the Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences recently featured an entire special issue in September 2024 dedicated to a number of these ongoing conversations (Larkins & Singh, 2024). Though they framed it as “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” many of the challenges and opportunities accounted for in that issue are also relevant and highly interrelated with our focus on environmental justice.

Previewing the Material

Introducing Environmental Justice Advocacy is meant to serve as a resource for faculty/instructors who will be teaching environmental justice at either the undergraduate (300-400) level or master’s level. This book is not meant as a stand-alone comprehensive textbook, but instead offers a series of readings to help students get a better sense of the nature and range of environmental justice advocacy and scholarship.

This book is divided into a few key parts. Following this introduction, the first set of chapters focuses on “Investigating Environmental Justice Issues and Stakeholders, Traditional and Novel.” Though in some ways these chapters appear to be categorically different, they are united insofar as they juxtapose fairly traditional areas of environmental justice issues with a focus on issues that are not typically described as part of environmental justice issues. Macon Thompson’s chapter, “Engaging Stakeholders for More Equitable Outcomes,” reflects on and offers a set of critical tools that are at the heart of doing environmental justice advocacy, since they concern the pivotal role of stakeholders and the variety of ways that a skilled environmental communicator can achieve success with the most relevant stakeholders. Ashlyn Johns’ chapter, “Eurocentric Beauty Standards as Environmental Injustice: The Way Our Societal Beauty Standards Increase Our Exposure to Toxic Ingredients,” explores the ways in which beauty standards and the mountain of chemical products designed to play on the need to attain such standards can result in systemic and toxic outcomes. Ashlyn’s and Macon’s chapters remind us that, whether engaged in formal stakeholder engagement or deciding on beauty products that we may use and/or recommend to others, environmental justice functions on numerous levels and we all play a part.

The second main section of this book is focused on “Utilizing Environmental Justice Approaches to Contest Colonial and Other Problematic Land Use Traditions.” These chapters are united by a focus on how the imposition of particular understandings of place, environment, and history onto understandings of land has powerful consequences. Taylor N. Johnson and Tarang Mishra’s chapter examines the environmentally problematic and unjust histories (and present) associated with ideas of environment and how such powerful ideologies are every bit as consequential in furthering the project of colonialism. Leanna Smithberger’s chapter attends to how a variety of land use understandings, including ones put forth and codified by legal actions, limits the potential possibilities for relation between human communities and the lands they inhabit. Notably, however, both chapters also emphasize the abilities for resistance, whether that be in the form of indigenous advocacy or novel expressions of hybrid agency, so that all power is not ceded in advance to those structures of power.

In the third main part of this book, “Forms of Doing/Voicing Environmental Justice Advocacy, we encounter ways in which the style of writing itself can be at the heart of environmental justice advocacy and scholarship. In Mariam Dames’ chapter, “Storytelling for Environmental Justice Advocacy,” Alex Davenport’s chapter, “Nature, Embodied: Performance, Resistance, and Environmental Justice,” and Katie Shedden’s chapter, “Tourism and the Environment: An Environmental Justice Autoethnography,” we see three approaches where form cannot (and should not) be separated from content. Though the constraints of this book project have kept us from having a more comprehensive inventory of such writing approaches, these chapters should remind us that not everyone engaged in environmental justice advocacy is doing so by way of scholarly, peer-reviewed writing and/or formal political statements and documents.

The final materials, at the end of this book, offer some potentially valuable supplemental material for the reader. In Appendix A, “Further Resources,” we provide two running lists–one of environmental justice undergraduate programs and one of environmental justice organizations (NGOs, nonprofits, etc.), to help see environmental justice action as it plays out in the public sphere. In Appendix B, “Tracking Updates,” we note those changes that we have made since first publishing this book. Finally, in Appendix C, “Licensing,” we describe the licensing choices put forth by the contributors.

In all, between this introduction, these seven chapters, and the subsequent appendices, we are only able to offer a glimpse into the vast network that is environmental justice. Nevertheless, we hope these chapters can offer readings and resources to help others find their way into environmental justice scholarship and/or advocacy.

Sincerely,

Matt, Doreen, and Grace

Harrisonburg, Virginia

James Madison University

February 2025

References

Cox, R. (2007). Nature’s ‘‘crisis disciplines’’: Does environmental communication have an ethical duty? Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 1(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030701333948

DeLuca, K. A wilderness environmentalism manifesto; Contesting the infinite self-absorption of humans. In R. Sandler & P. C. Pezzullo (Eds.), Environmental justice and environmentalism: The social justice challenge to the environmental movement. The MIT Press.

Gourlay, L. (2015). Open education as a ‘heterotopia of desire.’ Learning, Media & Technology, 40(3), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1029941

Kirkwood, A. (2012) Themed section: Enhancing learning and teaching in technology-poor contexts, Learning, Media and Technology, 37(4), 395-397, DOI: 10.1080/17439884.2012.696543

Larkins, M. L. & Singh, A. S. (Eds.). (2024). Practicing diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in environmental studies and sciences. [Special issue]. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 14(3), 443-628.

Mickel, B., & Scida, E. (2023). University of Virginia OER learning community guide. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Pezzullo, P. C. 7 Cox, R. (2018). Environmental communication and the public sphere (5th ed.). Sage.

Solnit, R. (2023). Difficult is not the same as impossible. In R. Solnit & T. Y. Lutunatabua (Eds.), Not too late: Changing the climate story from despair to possibility. Haymarket Books.

Media Attributions

- lan-johnson-aHlZv23P8YQ-unsplash

- There are quality arguments in favor of open educational resources (OER), as well as criticisms. The most substantial justification in favor of OERs is that it helps to reduce costs for students, which is a major factor in being able to attend college and having enough money for basic necessities. That being said, there are some criticisms that have been made about the shift to OERs. For instance, Gourlay (2015) has argued that the discourses around OERs continually reference it as liberatory and even revolutionary, yet such resources may ultimately serve to strengthen existing power relations. Other critics have argued that the aspirational visions of a more thoroughly infused global education does not take into account the differential resources of those who do not live in “technology rich” countries and communities: "Despite the increased participation in education anticipated within the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/index.shtml), there seems to be little likelihood of the educational systems in developing countries adopting technologies to support learning and teaching in the same way that their western counterparts have done" (Kirkwood, 2012, p. 395). ↵

- We opted not to make a general Call for Paper (CFP), in part because we needed a quick turnaround, from late September to early November for the first complete draft, and in part because we believe that our approach to environmental justice in this program, in relation to a communication and advocacy focus, is unique and thus warrants the spotlight on our alumni, given all of their excellent work over the past 10 years. ↵

- Part of establishing this movement involved pointing to aspects of traditional environmentalism that were at a minimum omitting the role played by identity positions such as race and class. A large number of environmental and environmental organizations have, in the intervening years, adopted these critiques to help their focus moving forward. Nonetheless, much of this coming together has been under the umbrella of alliances, and scholars like Kevin Deluca have cautioned against immediately labeling environmental advocacy as racist or classist, but also against the assumption that allies/alliances are always the right step: “It is important that environmental justice and wilderness environmental groups with different ideas retain their distinct identities and orientations even when forming alliances when it makes strategic sense” (2007, p. 47). ↵