Chapter 11: Development of Self and Identity

Identity Development Theory

A well-developed identity is comprised of goals, values, and beliefs to which a person is committed. It is the awareness of the consistency in self over time, the recognition of this consistency by others (Erikson, 1980). The process of identity development is both an individual and social phenomenon (Adams & Marshall, 1996). Much of this process is assumed during adolescence when cognitive development allows for an individual to construct a ‘theory of self’ (Elkind, 1998) based on exposure to role models and identity options (Erikson, 1980). Erikson (1968) believed this period of development to be an ‘identity crisis,’ a crucial turning point in which an individual must develop in one way or another, ushering the adolescent toward growth and differentiation. Identity is formed through a process of exploring options or choices and committing to an option based upon the outcome of their exploration. Failure to establish a well-developed sense of identity can result in identity confusion. Those experiencing identity confusion do not have a clear sense of who they are or their role in society.

Identity development is vital to a person’s understanding of self and participation in their social systems. Adams and Marshall (1996) established that identity formation provides five functions: a structure and order to self-knowledge; a sense of consistency and coherence to beliefs, goals, and self-knowledge; a sense of continuity for one’s history and future; goals and direction; a sense of personal control of their choices and outcomes.

Freud’s Theory

We begin with the often controversial figure, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resilience in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test the unconscious mind scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions are unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? Despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which to elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenged too.

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

Figure 11.1 Erik Erikson

Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development emphasizes the social nature of our development. His theory proposed that our psychosocial development takes place throughout our lifespan. Erikson suggested that how we interact with others is what affects our sense of self, or what he called the ego identity. He also believed that we are motivated by a need to achieve competence in certain areas of our lives.

According to psychosocial theory, we experience eight stages of development over our lifespan (Table 11.2), from infancy through late adulthood. At each stage, there is a conflict, or task, that we need to resolve. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy.

Table 11.2 Erikson’s psychosocial Stages of Development

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take the initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Video 11.6 Erikson’s Psychosocial Development explains all stages of this theory.

Trust vs. Mistrust

Erikson maintained that the first year to year and a half of life involves the establishment of a sense of trust. Infants are dependent and must rely on others to meet their basic physical needs as well as their needs for stimulation and comfort. A caregiver who consistently meets these needs instills a sense of trust or the belief that the world is a safe and trustworthy place. The caregiver should not worry about overindulging a child’s need for comfort, contact, or stimulation.

Consider the implications for establishing trust if a caregiver is unavailable or is upset and ill-prepared to care for a child, or if a child is born prematurely, is unwanted, or has physical problems that could make them less desirable to a parent. However, keep in mind that children can also exhibit strong resiliency to harsh circumstances. Resiliency can be attributed to certain personality factors, such as an easy-going temperament and receiving support from others. A positive and strong support group can help a parent and child build a strong foundation by offering assistance and positive attitudes toward the newborn and parent.

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

As the child begins to walk and talk, an interest in independence or autonomy replaces their concern for trust. The toddler tests the limits of what can be touched, said, and explored. Erikson believed that toddlers should be allowed to explore their environment as freely as safety allows and, in doing so, will develop a sense of independence that will later grow to self-esteem, initiative, and overall confidence. If a caregiver is overly anxious about the toddler’s actions for fear that the child will get hurt or violate others’ expectations, the caregiver can give the child the message that they should be ashamed of their behavior and instill a sense of doubt in their abilities. Parenting advice based on these ideas would be to keep your toddler safe, but let them learn by doing. A sense of pride seems to rely on doing rather than being told how capable one is (Berger, 2005).

Initiative vs. Guilt

While Erik Erikson was very influenced by Freud, he believed that the relationships that people have, not psychosexual stages, are what influence personality development. At the beginning of early childhood, the child is still in the autonomy versus shame and doubt stage (stage 2).

By age three, the child begins stage 3: initiative versus guilt. The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiate action. Children are curious at this age and start to ask questions so that they can learn about the world. Parents should try to answer those questions without making the child feel like a burden or implying that the child’s question is not worth asking.

These children are also beginning to use their imagination (remember what we learned when we discussed Piaget!). Children may want to build a fort with cushions from the living room couch, open a lemonade stand in the driveway, or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Another way that children may express autonomy is in wanting to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being overly critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pale in comparison to the smiling face of a five-year-old emerging from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas!

That said, it is important that the parent does their best to kindly guide the child to the right actions. If the child does leave those soggy washrags in the sink, have the child help clean them up. It is possible that the child will not be happy with helping to clean, and the child may even become aggressive or angry, but it is important to remember that the child is still learning how to navigate their world. They are trying to build a sense of autonomy, and they may not react well when they are asked to do something that they had not planned. Parents should be aware of this, and try to be understanding, but also firm. Guilt for a situation where a child did not do their best allows a child to understand their responsibilities and helps the child learn to exercise self-control (remember the marshmallow test). The goal is to find a balance between initiative and guilt, not a free-for-all where the parent allows the child to do anything they want to. The parent must guide the child if they are to have a successful resolution in this stage.

Watch it

Video 11.7 Movies, television, and media, in general, provide many examples of psychosocial development. The movie clips in this video demonstrate Erikson’s third stage of development, initiative versus guilt. What other examples can you think of to demonstrate young children developing a sense of autonomy?

Industry vs. Inferiority

Erikson believes that children’s greatest source of personality development comes from their social relationships. So far, we have seen 3 psychosocial stages: trust versus mistrust (ages birth – 18 months), autonomy versus shame and doubt (ages 18 months – 3 years), and initiative versus guilt (ages 3 years – around 6 years).

According to Erikson, children in middle childhood are very busy or industrious. They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, and achieving. This is a very active time and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with friends. Erikson believed that if these industrious children view themselves as successful in their endeavors, they will get a sense of competence for future challenges. If instead, a child feels that they are not measuring up to their peers, feelings of inferiority and self-doubt will develop. These feelings of inferiority can, according to Erikson, lead to an inferiority complex that lasts into adulthood.

To help children have a successful resolution in this stage, they should be encouraged to explore their abilities. They should be given authentic feedback as well. Failure is not necessarily a horrible thing according to Erikson. Indeed, failure is a type of feedback that may help a child form a sense of modesty. A balance of competence and modesty is ideal for creating a sense of competence in the child.

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Erik Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of adolescence was establishing an identity. Erikson referred to life’s fifth psychosocial task as one of identity versus role confusion when adolescents must work through the complexities of finding one’s own identity. This stage includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. During adolescence, many individuals experience a psychological moratorium, where teens put a on hold commitment to an identity while exploring the options.

Individual identity development is influenced by how they resolved all of the previous childhood psychosocial crises, and this adolescent stage is a bridge between the past and the future, childhood, and adulthood. Thus, in Erikson’s view, an adolescent’s central questions are, “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Identity formation was highlighted as the primary indicator of successful development during adolescence (in contrast to role confusion, which would be an indicator of not successfully meeting the task of adolescence). This crisis is resolved positively with identity achievement, when adolescents have reconsidered the goals and values of their parents and culture. Some adolescents adopt the values and roles that their parents expect for them. Other teens develop identities that are in opposition to their parents but align with a peer group. This change is common as peer relationships become a central focus in adolescents’ lives.

The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).

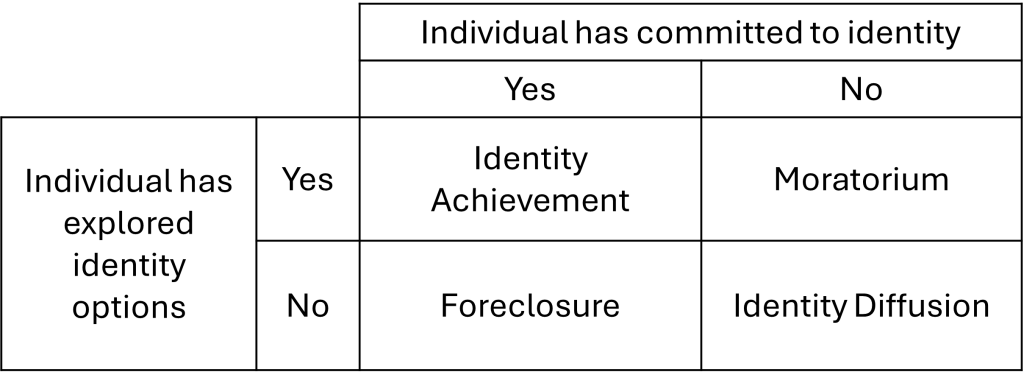

Marcia’s Identity Statuses

Expanding on Erikson’s theory, Marcia (1966) described identity formation during adolescence as involving both exploration and commitment with respect to ideologies and occupations (e.g., religion, politics, career, relationships, gender roles). Identity development begins when individuals identify with role models who provide them with options to explore for whom they can become. As identity development progresses, adolescents are expected to make choices and commit to options within the confines of their social contexts. In some cases, options are not provided or are limited, and the individual will fail to commit or will commit without the opportunity to explore various options (Marcia, 1980).

Video 11.8 Macia’s Stages of Adolescent Identity Development summarizes the various identity statuses and how an individual may move through them.

Figure 11.2 Marcia’s identity statuses. Adapted from Discovering the Lifespan, by R. S. Feldman, 2009.

The least mature status, and one common in many children, is identity diffusion. Identity diffusion is a status that characterizes those who have neither explored the options nor made a commitment to an identity. Marcia (1980) proposed that when individuals enter the identity formation process, they have little awareness or experience with identity exploration or the expectation to commit to an identity. This period of identity diffusion is typical of children and young adolescents, but adolescents are expected to move out of this stage as they are exposed to role models and experiences that present them with identity possibilities. Those who persist in this identity may drift aimlessly with little connection to those around them or have little sense of purpose in life. Characteristics associated with prolonged diffusion include having low self-esteem, being easily influenced by peers, lacking of meaningful friendships, having little commitment, or fortitude in activities or relationships, and being self-absorbed and self-indulgent.

Those in identity foreclosure have committed to an identity without having explored the options. Often, younger adolescence will enter a phase of foreclosure where they may, at least preliminarily, commit to an identity without an investment in the exploration process. This commitment is often a response to anxiety about uncertainty or change during adolescence or pressure from parents, social groups, or cultural expectations. It is expected that most adolescents will progress beyond the foreclosure phase as they can think independently, and we multiple identity options. However, sometimes foreclosure will persist into late adolescence or even adulthood.

In some cases, parents may make decisions for their children and do not grant the teen the opportunity to make choices. In other instances, teens may strongly identify with parents and others in their life and wish to follow in their footsteps. Characteristics associated with prolonged foreclosure include being well-behaved and obedient children with a high need for approval, having parents with an authoritarian parenting style, having low levels of tolerance or acceptance of change, having high levels of conformity, and being a conventional thinker.

During high school and college years, teens and young adults move from identity diffusion and foreclosure toward moratorium and achievement. The most significant gains in the development of identity are in college, as college students are exposed to a greater variety of career choices, lifestyles, and beliefs. This experience is likely to spur on questions regarding identity. A great deal of the identity work we do in adolescence and young adulthood is about values and goals, as we strive to articulate a personal vision or dream for what we hope to accomplish in the future (McAdams, 2013).

Identity moratorium is a status that describes those who are actively exploring in an attempt to establish identity but have yet to have made any commitment. This time can be an anxious and emotionally tense period as the adolescent experiments with different roles and explores various beliefs. Nothing is guaranteed, and there are many questions, but few answers. This moratorium phase is the precursor to identity achievement. During the moratorium period, it is normal for adolescents to be rebellious and uncooperative, avoid dealing with problems, procrastinate, experience low self-esteem, and feel anxious and uncertain about decisions.

Identity achievement refers to those who, after exploration, have committed. Identity achievement is a long process and is not often realized by the end of adolescence. Individuals that do reach identity achievement feel self-acceptance, stable self-definition, and are committed to their identity.

While Marcia’s statuses help us understand the process of developing identity, there are several criticisms of this theory. First, identity status may not be global; different aspects of your identity may be in different statuses. An individual may be in multiple identity statuses at the same time for different aspects of identity. For example, one could be in foreclosure for their religious identity, but in moratorium for career identity, and achievement for gender identity.

Further, identity statuses do no always develop in the sequence described above, although it is the most common progression. Not all people will reach identity achievement in all aspects of their identity, and not all may remain in identity achievement. There may be a third aspect of identity development, beyond exploration and commitment, and that is the reconsideration of commitment. This addition would create a fifth status, searching moratorium. This status is a re-exploring after a commitment has been made (Meesus et al., 2012). It is not usual that commitments to aspects of our identity may change as we gain experiences, and more options become available to explore. This searching moratorium may continue well into adulthood.

Supporting Identity Development

As the process of identity development can be a confusing and challenging period, how can adults support adolescents through this process? First, affirm that the anxiety, doubts, and confusion are reasonable and that most teens do not complete identity achievement before graduating high school. Exposing adolescents to various role models can help them imagine different roles or options for their future selves. Role models can come from within the family, schools, or community. Adults should talk with adolescents about their values, goals, and identities to help build awareness. They may be interested to know how others made decisions while developing their own identities. Finally, support the commitments that adolescents have made. Identity commitments can help someone feel grounded and less confused while they engage in identity exploration.

teens put a on hold commitment to an identity while exploring the options

a status that characterizes those who have neither explored the options nor made a commitment to an identity

individuals who have committed to an identity without having explored the options

status that describes those who are actively exploring in an attempt to establish identity but have yet to have made any commitment

refers to those who, after exploration, have committed

re-exploring after a commitment has been made