Chapter 6: Physical Development

Nutrition

Infant Nutrition

Good nutrition in a supportive environment is vital for an infant’s healthy growth and development. Remember, from birth to 1 year, infants triple their weight and increase their height by half, and this growth requires good nutrition. For the first 6 months, babies are fed breast milk or formula, both of which provide proper nutrition. Starting good nutrition practices early can help children develop healthy dietary patterns. Infants need to receive nutrients to fuel their rapid physical growth. Malnutrition during infancy can result in not only physical but also cognitive and social consequences (Galler et al., 2021). Without proper nutrition, infants cannot reach their physical potential.

Breast Milk and Formula Feeding

Breast milk is considered an ideal diet for newborns due to the nutrition makeup of colostrum and subsequent breastmilk production. Colostrum, the milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth, has been described as “liquid gold. Colostrum is packed with nutrients and other important substances that help the infant build up their immune system. Most babies will get all the nutrition they need through colostrum during the first few days of life (CDC, 2018). Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development. It provides a source of iron more easily absorbed in the body than the iron found in dietary supplements, it provides resistance against many diseases, it is more easily digested by infants than formula.

The reason infants need such a high-fat content is the process of myelination which requires fat to insulate the neurons. Therefore, there has been some research, including meta-analyses, to show that consuming breast milk is connected to some long-term cognitive advantages (Lenehan et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2021). Preterm infants particularly benefit from consuming breast milk which contributes to cardiovascular and neurological health (Kumar et al., 2017).

For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula-fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who consume breast milk have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). For all of these reasons, it is recommended that infants consume breast milk exclusively until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year (CDC, 2023).

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies farther apart. Parents who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer, especially among higher-risk racial and ethnic groups (Islami et al., 2015). Other studies suggest that women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer (Titus-Ernstoff, Rees, Terry, & Cramer, 2010), and reduced risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (Gunderson, et al., 2015), and rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson, Mandl, Hankinson, & Grodstein, 2004).

A historic look at breastfeeding

The use of wet nurses, or lactating women, hired to nurse others’ infants, during the middle ages eventually declined, and mothers increasingly breastfed their own infants in the late 1800s. In the early part of the 20th century, breastfeeding began to go through another decline, and by the 1950s it was practiced less frequently by middle class, more affluent mothers as formula began to be viewed as superior to breast milk. In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was again a greater emphasis placed on natural childbirth and breastfeeding and the benefits of breastfeeding were more widely publicized. Gradually, rates of breastfeeding began to climb, particularly among middle-class educated mothers who received the strongest messages to breastfeed.

Today, new mothers receive consultation from lactation specialists before being discharged from the hospital to ensure that they are informed of the benefits of breastfeeding and given support and encouragement to get their infants accustomed to taking the breast. This does not always happen immediately, and first-time mothers, especially, can become upset or discouraged. In this case, lactation specialists and nursing staff can encourage the mother to keep trying until the baby and mother are comfortable with the feeding.

Most parents who breastfeed in the United States stop breastfeeding at about 6-8 weeks, often in order to return to work outside the home (United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2011). Parents can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time, but some parents find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding parents by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. And the public support of breastfeeding is sometimes lacking. Parents in Canada are more likely to breastfeed than are those in the United States, and the Canadian health recommendation is for breastfeeding to continue until 2 years of age. Facilities in public places in Canada such as malls, ferries, and workplaces provide more support and comfort for the breastfeeding parent and child than found in the United States. In addition to the nutritional and health benefits of breastfeeding, breast milk is free!

Links to Learning

- Watch this video from the Psych SciShow “Bad Science: Breastmilk and Formula” to learn about research related to both breastfeeding and formula-feeding.

- To learn more about breastfeeding, visit this resource from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources: Your Guide to Breastfeeding.

- Visit Kids Health on Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding to learn more about the benefits and challenges of each. Click on the speaker icon to listen to the narration of the article if you would like.

However, there are occasions where parents may be unable to breastfeed babies or feed their babies breast milk for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons, or simply choose not to breastfeed. For example, breastfeeding generally does not work:

- when the baby is adopted

- when the biological mother has a transmissible disease such as tuberculosis or HIV

- when the mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control)

- when the infant was born to (or adopted by) a family with two fathers and the surrogate mother is not available to breastfeed

- when there are attachment issues between mother and baby

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process

- when the baby and mother are attached but the mother does not produce enough breast-milk

One early argument given to promote the practice of breastfeeding (when health issues are not the case) is that it promotes bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, this does not seem to be a unique case. Breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally (Ferguson & Woodward, 1999). This is good news for mothers who may be unable to breastfeed for a variety of reasons and for fathers who might feel left out as a result.

Although breast milk is an ideal source of nutrition for infants, it is not the only option for parents. Formula may be an option for families in which breast milk is not an option. Infant formula contains the nutrients that infants need to grow and develop. While providing breast milk is typically recommended, there is a movement to support all parents regardless of how they feed their infants.

Introducing Solid Foods

Breast milk or formula is the only food a newborn needs, and the American Academy of Pediatrics (2022) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months after birth. Solid foods can be introduced from around six months onward when babies develop stable sitting and oral feeding skills but should be used only as a supplement to breast milk or formula. By six months, the gastrointestinal tract has matured, solids can be digested more easily, and allergic responses are less likely.

Though infants usually start eating solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age, more and more solid foods are consumed by a growing toddler. Pediatricians recommended introducing foods one at a time, and for a few days, in order to identify any potential food allergies. Toddlers may be picky at times, but it remains important to introduce a variety of foods and offer food with essential vitamins and nutrients, including iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies on infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can certainly be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequate means to sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many of these countries, such conditions were not available and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula which made them become sick with diarrhea and become dehydrated. These conditions continue today and now many hospitals prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in efforts to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many of these mothers do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported in order to promote this practice.

The World Health Organization (2018) recommends:

- initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

- exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life

- introduction of solid foods at six months together with continued breastfeeding up to two years of age or beyond

Link to Learning

The consumption of breast milk could save the lives of millions of infants each year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), yet fewer than 40 percent of infants are breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months of life. Because of the great benefits of breastfeeding, WHO, UNICEF, and other national organizations are working together with the government to step up support for breastfeeding globally.

Find out more statistics and recommendations for breastfeeding at the WHO’s 10 facts on breastfeeding. You can also learn more about efforts to promote breastfeeding in Peru: “Protecting Breastfeeding in Peru”.

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed. After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor, or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

Watch It

Video 6.4 Watch this video to learn more about the signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor and marasmus.

Nutritional Concerns in Childhood

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 5 American children between the ages of 2 and 5 are overweight or obese. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends a number of steps to take to help reduce the chances of obesity in young children. Removing high-calorie low-nutrition foods from the diet, offering whole fruits and vegetables instead of just juices, and getting kids active are just some of the recommendations that they make. Muckelbauer and colleagues (2009) found that increasing water consumption in school-aged children by just 220ml (just under 8 oz) per day decreased the risk of obesity by 31%. Finally, the AAP suggests that parents can begin offering milk with a lower fat percentage (2%, 1%, or skim milk) to 2-year-olds. The switch to lower fat milk may help avoid some of the obesity issues discussed above. Parents should avoid giving the child too much milk as calcium interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well.

Caregivers (whether parents or non-parents) need to keep in mind that they are setting up taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to high-fat, very sweet, and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods that have more subtle flavors such as fruits and vegetables. Lack of a healthy diet may lead to obesity during this and future stages. Offering a diet of diverse food options, limiting foods with high calories but low nutritional value, and limiting high-calorie drink options can all contribute greatly to a child’s health during this stage of life.

Caregivers who have established a feeding routine with their child can find the normal reduction in appetite a bit frustrating and become concerned that the child is going to starve. However, by providing adequate, sound nutrition, and limiting sugary snacks and drinks, the caregiver can be assured that 1) the child will not starve, and 2) the child will receive adequate nutrition.

Tips for Establishing Healthy Eating Patterns

Consider the following advice about establishing eating patterns for years to come (Rice, F.P., 1997). Notice that keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition, and not engaging in power struggles over food are the main goals.

1. Don’t try to force your child to eat or fight over food. Of course, it is impossible to force someone to eat. But the real advice here is to avoid turning food into some kind of ammunition during a fight. Do not teach your child to eat to or refuse to eat in order to gain favor or express anger toward someone else.

2. Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help to realize that appetites do vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat.

3. Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Mealtimes should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress.

4. No short-order chefs. While it is fine to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when they are hungry and a meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” continuously can help create an appetite for whatever is being served.

5. Limit choices. If you give your preschool-aged child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or choose whatever their sibling does not choose!

6. Serve balanced meals. This tip encourages caregivers to serve balanced meals. A box of macaroni and cheese is not a balanced meal. Meals prepared at home tend to have better nutritional value than fast food or frozen dinners. Prepared foods tend to be higher in fat and sugar content as these ingredients enhance taste and profit margin because fresh food is often more costly and less profitable. However, preparing fresh food at home is not costly. It does, however, require more activity. Preparing meals and including the children in kitchen chores can provide a fun and memorable experience.

7. Don’t bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetables by promising dessert is not a good idea. For one reason, the child will likely find a way to get the desert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in), and for another reason, because it teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. A child, for example, may learn the broccoli they have enjoyed is seen as yucky by others unless it’s smothered in cheese sauce!

To what extent do these tips address cultural practices? How might these tips vary by culture?

Childhood Obesity

Nearly 20 percent of school-aged American children are obese. This is defined as being at least 20 percent over their ideal weight. The percentage of obesity in school-aged children has increased substantially since the 1960s, and it continues to increase. This is true in part because of the introduction of a steady diet of television and other sedentary activities. In addition, we have come to emphasize high fat, fast foods as a culture. Pizza, hamburgers, chicken nuggets, and “Lunchables” with soda have replaced more nutritious foods as staples.

School Lunches

School lunches must meet the applicable recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. These guidelines state that no more than 30 percent of an individual’s calories should come from fat and less than 10 percent from saturated fat. Regulations also state that school lunches must provide one-third of the recommended dietary allowances of protein, Vitamin A, Vitamin C, iron, calcium, and calories. School lunches must meet federal nutrition requirements over the course of one week’s worth of lunches. However, local school food authorities may make decisions about which specific foods to serve and how they are prepared.

Many children in the United States buy their lunches in the school cafeteria, so it might be worthwhile to look at the nutritional content of school lunches. You can obtain this information through your local school district’s website. An example of a school menu and nutritional analysis from a school district in north-central Texas is a meal consisting of pasta alfredo, breadstick, peach cup, tomato soup, and a brownie, and 2% milk. Students may also purchase chips, cookies, or ice cream along with their meals. Many school districts rely on the sale of dessert and other items in the lunchrooms to make additional revenues and many children purchase these additional items so our look at their nutritional intake should also take this into consideration.

Consider another menu from an elementary school in the state of Washington. This sample meal consists of a chicken burger, tater tots, fruit and veggies, and 1% or nonfat milk. This meal is also in compliance with Federal Nutrition Guidelines but has about 300 fewer calories. And, children are not allowed to purchase additional desserts such as cookies or ice cream.

Michelle Obama has been a recent advocate for nutritional school lunches. Since the Healthy, Hunger-Free Act of 2010, she has worked diligently to defend the importance of healthy school lunches but has largely not been successful in her efforts. Schools in the United States are having difficulty enforcing nutrition values in fear of being wasteful because some of the new standards such as whole grains, more vegetables, and reduced sodium levels initially resulted in fewer children eating their lunches. Children are eating 16% more vegetables and 23% more fruit during lunches, and over 90% of schools report that they are meeting the new nutritional guidelines.

One consequence of childhood obesity is that children who are overweight tend to be ridiculed and teased by others. This can certainly be damaging to their self-image and popularity. In addition, obese children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries, and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke in adulthood. It may be difficult for a child who is obese to become a non-obese adult. In addition, the number of cases of pediatric diabetes has risen dramatically in recent years.

Dieting is not really the solution to childhood obesity. If your diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain the weight. Increased activity is much more effective in lowering the weight and improving the child’s health and psychological well-being. Exercise reduces stress and being an overweight child, subjected to the ridicule of others can certainly be stressful. Parents should take caution against emphasizing diet alone to avoid the development of any obsession about dieting that can lead to eating disorders as teens.

Exercise and Sports

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. Nearly 3 million children play soccer in the United States (United States Youth Soccer, 2012). This activity promises to help children build social skills, improve athletically, and learn a sense of competition. However, it has been suggested that the emphasis on competition and athletic abilities can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U. S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling during practice and to allow children to play more freely and to choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

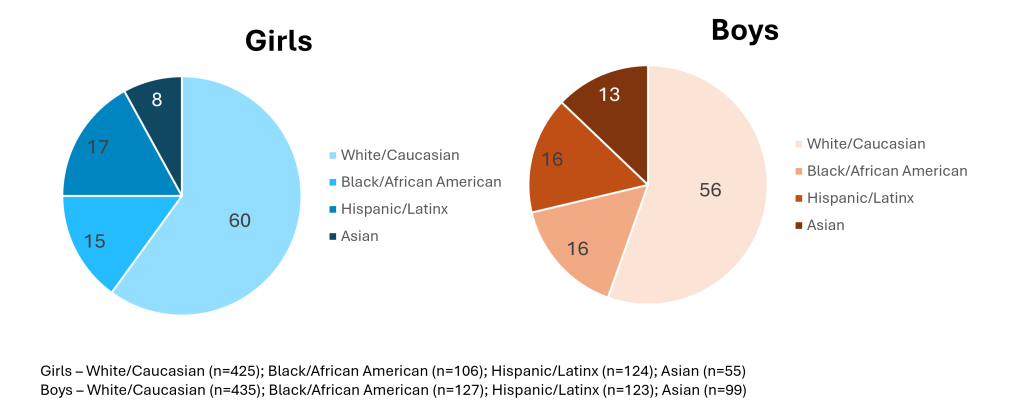

Yet, a study on children’s sports in the United States (Sabo & Veliz, 2008) has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports. Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport (see Figure 6.9). They also found that fathers may not be providing their daughters as much support as they do their sons.

While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentor who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches, and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Sabo and Veliz (2008) also found that children in suburban neighborhoods had much higher participation in sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. In addition, White girls and boys participated in organized sports at higher rates than minority children (see Figure 6.10).

Figure 6.9 Participation in organized sports (%) by gender.

Figure 6.10 Participation in organized sports (%) by race and ethnicity.

Nutrition Concerns During Adolescence

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development.

One of the reasons for poor nutrition is anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in-person and via social media).

Much research has been conducted on the psychological ramifications of body image on adolescents. Modern-day teenagers are exposed to more media on a daily basis than any generation before them. Recent studies have indicated that the average teenager watches roughly 1500 hours of television per year, and 70% use social media multiple times a day. As such, modern-day adolescents are exposed to many representations of ideal, societal beauty. The concept of a person being unhappy with their own image or appearance has been defined as body dissatisfaction. In teenagers, body dissatisfaction is often associated with body mass, low self-esteem, and atypical eating patterns. Scholars continue to debate the effects of media on body dissatisfaction in teens. What we do know is that two-thirds of U.S. high school girls are trying to lose weight and one-third think they are overweight, while only one-sixth are actually overweight (MMWR, June 10, 2016).

Eating Disorders

Dissatisfaction with body image can explain why many teens, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest diet pills to lose weight and why boys may take steroids to increase their muscle mass. Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (NIMH, 2019). Eating disorders affect everyone, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, some men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular.

Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2019). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with women without. The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Video 6.5 Eating Disorders explains the symptoms of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, as well as common treatments.

Anorexia Nervosa

People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, often exercise excessively, and/or may force themselves to vomit or use laxatives to lose weight. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. While many people with this disorder die from complications associated with starvation, others die of suicide.

For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk of heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental illnesses.

Bulimia Nervosa

People with bulimia nervosa have recurrent and frequent episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food and feeling a lack of control over these episodes. This binge-eating is followed by behavior that compensates for overeating such as forced vomiting, excessive use of laxatives or diuretics, fasting, excessive exercise, or a combination of these behaviors. People with bulimia nervosa may be slightly underweight, normal weight, or overweight.

The binging and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestive system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Binge-Eating Disorder

People with binge-eating disorder lose control over his or her eating. Unlike bulimia nervosa, periods of binge-eating are not followed by purging, excessive exercise, or fasting. As a result, people with binge-eating disorder often are overweight or obese. Binge-eating disorder is the most common eating disorder in the U.S.

Eating Disorders Treatment

To treat eating disorders, getting adequate nutrition, and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2019). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding their child. To eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Link to Learning

Visit National Eating Disorders Association to learn more about eating disorders.

a condition that results from eating a diet in which one or more nutrients are deficient

the first secretion from the mammary glands after giving birth, rich in antibodies

starvation due to a lack of calories and protein

also known as the “disease of the displaced child,” results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein

a person’s idea of how his or her body looks

negative subjective evaluation of the weight and shape of one’s own body, which may predict the onset, severity, and treatment outcomes of eating disorders

extreme concern with becoming more muscular

an eating disorder characterized by self- starvation. Affected individuals voluntarily under-eat and often over-exercise, depriving their vital organs of nutrition. Anorexia can be fatal

an eating disorder characterized by binge eating and subsequent purging, usually by induced vomiting and/or use of laxative

an eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food (often very quickly and to the point of discomfort); a feeling of a loss of control during the binge; experiencing shame, distress, or guilt afterwards; and not regularly using unhealthy compensatory measures (e.g., purging) to counter the binge eating. It is the most common eating disorder in the United States