Chapter 12: Play and Peer Relationships

Peer Relationships

Peer relationships are a significant part of life, but they are especially important during childhood and adolescence. Interaction with another child similar in age and knowledge develops many valuable skills for emotional intelligence, conflict management, compromise, bargaining, and taking turns (Bukowski et al., 2011). Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support outside of their families.

However, peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin et al., 2011). Being accepted by other children is an essential source of affirmation and self-esteem. Peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems, especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior (Coie et al., 1982; Rubin et al., 2011). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures.

Adolescent Peer Relationships

As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families (Afshordi & Liberman, 2020; Van Der Aar et al., 2018). Peer relationships are increasingly important to adolescents, and they offer opportunities for personal growth, identity development, and social comparison (Sebastian et al., 2008; Van Der Aar et al., 2018).

Friendships

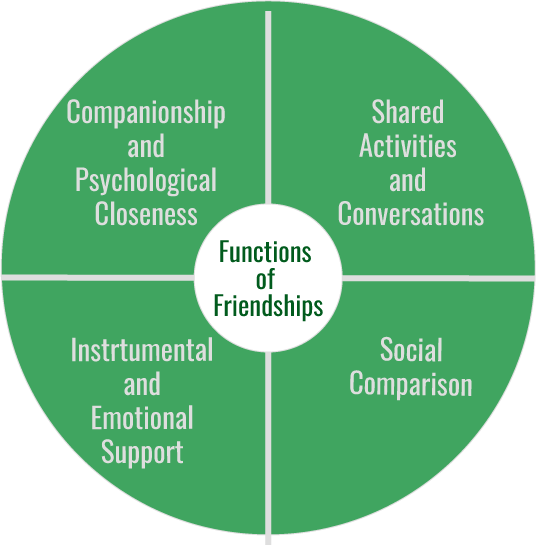

Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities and playtime, whereas adolescents’ ideas of friendship are rooted in the intimate exchange of thoughts and feelings (Crosnoe, 2000). More emphasis is placed on the quality of a relationship and the amount of psychological intimacy, vulnerability, trust, and loyalty shared between peers (Crosnoe, 2000). Peers serve a few functions, but they are primarily an essential source of social support and companionship during adolescence. Adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or who have conflict-filled peer relationships (Shin et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Functions of friendship. By Florida State College at Jacksonville, licensed under CC-BY 4.0 .

Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behavior, attitudes, and interests; it is easy for people to get along with those who are like them (Donlan et al., 2015). Over time, adolescents become even more similar to each other as they learn which behaviors and thought patterns earn them approval from their peers (Donlan et al., 2015; Veenstra et al, 2013). Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others.

Peer Pressure

Peers can serve as both positive and negative influences on an adolescent. Peer pressure can be thought of as a group influencing an individual to conform to something, whether that be a belief or a behavior (American Psychological Association, 2018a). Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family (Jayanthi, 2013). This might look like friends pushing a teenager to do something that their parents would disapprove of, such as using drugs or cheating on an exam. Deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011) is the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior through signs of approval, like laughing, that increase the likelihood of that problem behavior happening again. Positive peer pressure, though, can influence an adolescent to engage in good behaviors, such as physical activity, studying, and volunteering (Boruah, 2016).

Romantic Relationships

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. Initially, same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence (Molloy et al., 2014). Romantic relationships often form within these new mixed-sex groups (Connolly et al., 2003).

Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships (or lack thereof) than to friendships, family, or school (Connolly et al., 2004; Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, emotional and behavioral adjustment, and changes with family and peers (Collins, 2003; Flynn et al., 2014; Norona et al, 2017).

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality (Collins, 2003). Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancy (Collins, 2003; Rose, 2005). However, sexuality encompasses a wide range of values, beliefs, behaviors, and identities—not just sexual activity (Agocha et al., 2014).

a group influencing an individual to conform to something, whether that be a belief or a behavior

the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior through signs of approval, like laughing, that increase the likelihood of that problem behavior happening again