2 Communication and Perception

Introduction

Think back to the first day of classes. Did you plan for what you were going to wear? Did you get the typical school supplies together? Did you try to find your classrooms ahead of time or look for the syllabus online? Did you look up your professors on an online professor evaluation site? Based on your answers to these questions, your professors could form an impression of who you are as a student. However, would that perception be accurate? Would it match up with how you see yourself as a student? Moreover, perception, of course, is a two-way street. You also formed impressions about your professors based on their appearance, dress, organization, intelligence, and approachability. The impressions that both teacher and student make on the first day help set the tone for the rest of the semester.

As we go through our daily lives we perceive all sorts of people and objects, and we often make sense of these perceptions by using previous experiences to help filter and organize the information we take in (Broadbent, 2013). Sometimes we encounter new or contradictory information that changes the way we think about a person, group, or object. The perceptions that we make of others and that others make of us affect how we communicate and act. We will learn about the perception process, how we perceive others, how we perceive and present ourselves, and how we can improve our perceptions.

2.1 Perception Process

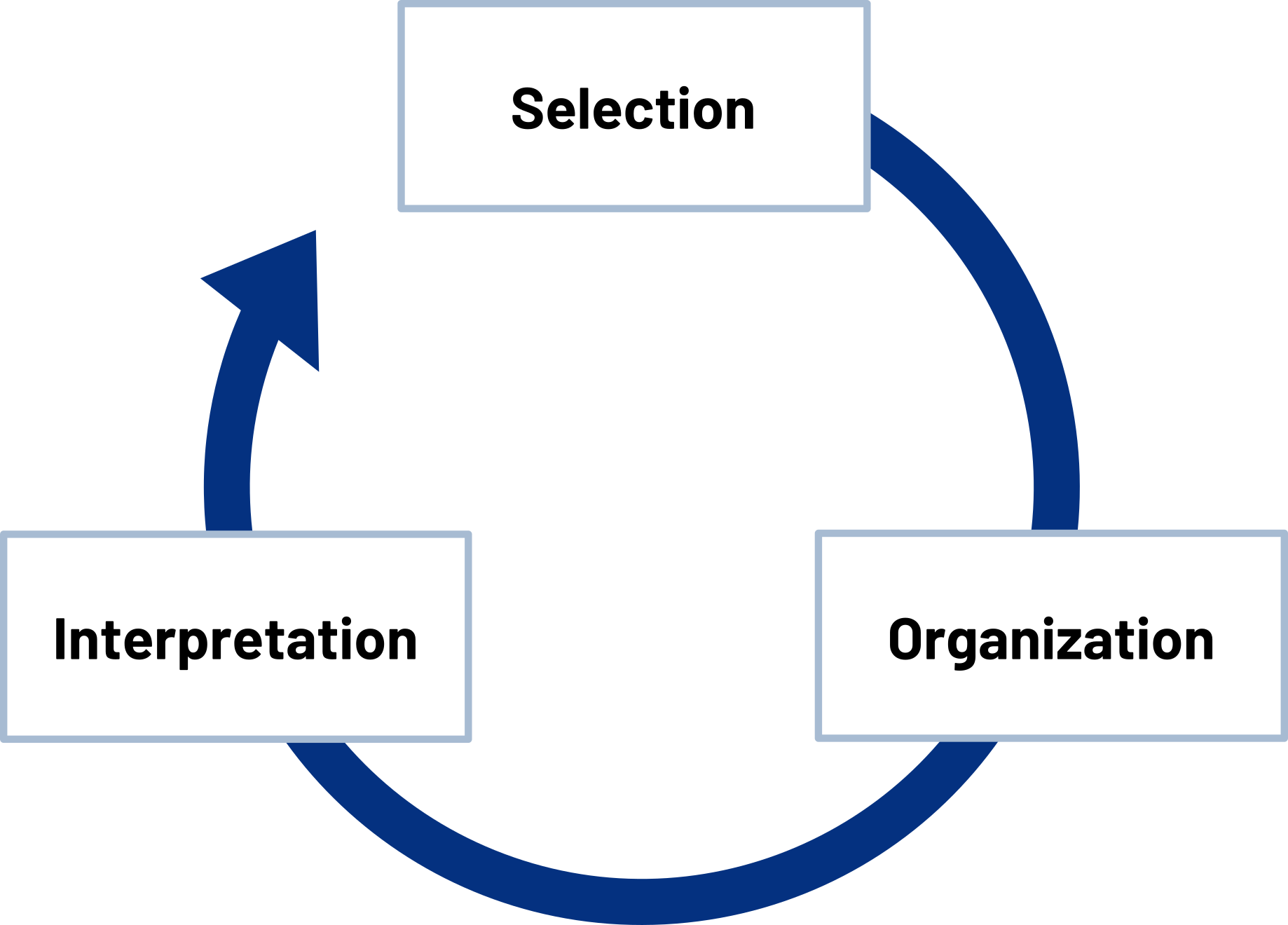

Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information (Wertz, 1982). This process includes the perception of select stimuli that pass through our perceptual filters. These stimuli are organized into our existing structures and patterns and interpreted based on previous experiences. Although perception is a largely cognitive and psychological process, how we perceive the people and objects around us affects our communication. We respond differently to an object or person that we perceive favorably than we do to something we find unfavorable (Wertz, 1982). How do we filter through the mass amounts of incoming information, organize it, and make meaning from what makes it through our perceptual filters and into our social realities?

Selecting Information

We take in information through all five of our senses, but our perceptual field (the world around us) includes so many stimuli that it is impossible for our brains to process and make sense of it all. As information comes in through our senses, various factors influence what actually continues through the perception process (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Selecting is the first part of the perception process, in which we focus our attention on certain incoming sensory information. Think about how, out of many other possible stimuli to pay attention to, you may hear a familiar voice in the hallway, see a pair of shoes you want to buy from across the mall, or smell something cooking for dinner when you get home from work. We quickly cut through and push to the background all kinds of sights, smells, sounds, and other stimuli, but how do we decide what to select and what to leave out?

We tend to pay attention to information that is salient. Salience is the degree to which something attracts our attention in a particular context. The thing attracting our attention can be abstract, like a concept, or concrete, like an object. For example, a person’s identity as a Native American may become salient when they are protesting at the Columbus Day parade in Denver, Colorado. A bright flashlight shining in your face while camping at night is sure to be salient. The degree of salience depends on three features (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). We tend to find salient things that are visually or aurally stimulating and things that meet our needs or interests. Lastly, expectations affect what we find salient.

Visual and Aural Stimulation

It is probably not surprising to learn that visually and/or aurally stimulating things become salient in our perceptual field and get our attention (Wertz, 1982). Creatures ranging from fish to hummingbirds are attracted to things like silver spinners on fishing poles or red and yellow bird feeders. Having our senses stimulated is not always a positive thing though. Think about the couple that will not stop talking during the movie or the upstairs neighbor whose subwoofer shakes your ceiling at night. In short, stimuli can be attention getting in a productive or distracting way. As communicators, we can use this knowledge to our benefit by minimizing distractions when we have something important to say. It is probably better to have a serious conversation with a significant other in a quiet place rather than a crowded food court.

Needs and Interests

We tend to pay attention to information that we perceive to meet our needs or interests in some way. This type of selective attention can help us meet instrumental needs and get things done. When you need to speak with a financial aid officer about your scholarships and loans, you sit in the waiting room and listen for your name to be called. Paying close attention to whose name is called means you can be ready to start your meeting and get your business handled. When we do not think certain messages meet our needs, stimuli that would normally get our attention may be completely lost. Imagine you are in the grocery store and you hear someone say your name. You turn around, only to hear that person say, “Finally! I said your name three times. I thought you forgot who I was!” A few seconds before, when you were focused on figuring out which kind of orange juice to get, you were attending to the various pulp options to the point that you tuned other stimuli out, even something as familiar as the sound of someone calling your name.

We also find salient information that interests us. Of course, many times, stimuli that meet our needs are also interesting, but it is worth discussing these two items separately because sometimes we find things interesting that do not necessarily meet our needs (Wertz, 1982). We have all been sucked into a television show, video game, or random project and paid attention to that at the expense of something that actually meets our needs (like cleaning, or spending time with a significant other). Paying attention to things that interest us but do not meet specific needs seems like the basic formula for procrastination with which we are all familiar.

Expectations

The relationship between salience and expectations is a little more complex. We can find expected things salient and find things that are unexpected salient (Wertz, 1982). While this may sound confusing, a couple examples should illustrate this point. If you are expecting a package to be delivered, you might notice the slightest noise of a truck engine or someone’s footsteps approaching your front door. Since we expect something to happen, we may be extra tuned in to clues that it is coming. In terms of the unexpected, if you have a shy and soft-spoken friend who you overhear raising the volume and pitch of his voice while talking to another friend, you may pick up on that and assume that something out of the ordinary is going on. For something unexpected to become salient, it has to reach a certain threshold of difference. If you walked into your regular class and there were one or two more students there than normal, you may not even notice. If you walked into your class and there was someone dressed up as a wizard, you would probably notice. Therefore, if we expect to experience something out of the routine, like a package delivery, we will find stimuli related to that expectation salient. If we experience something that we were not expecting and that is significantly different from our routine experiences, then we will likely find it salient. We can also apply this concept to our communication.

Organizing Information

Organizing is the second part of the perception process, in which we sort and categorize information that we perceive based on innate and learned cognitive patterns. Three ways we sort things into patterns are by using proximity, similarity, and difference (Coren & Girgus, 1980). In terms of proximity, we tend to think that things that are close together go together. For example, have you ever been waiting to be helped in a business and the clerk assumes that you and the person standing beside you are together? The slightly awkward moment usually ends when you and the other person in line look at each other, then back at the clerk, and one of you explains that you are not together. Even though you may have never met that other person in your life, the clerk used a basic perceptual organizing cue to group you together because you were standing in proximity to one another.

We also group things together based on similarity. We tend to think similar-looking or similar-acting things belong together (Ma, 2012). We also organize information that we take in based on difference. In this case, we assume that the item that looks or acts different from the rest does not belong with the group. Perceptual errors involving people and assumptions of difference can be especially awkward, if not offensive.

These strategies for organizing information are so common that they are built into how we teach our children basic skills and how we function in our daily lives (Ma, 2012). We probably all had to look at pictures in grade school and determine which things went together and which thing did not belong. If you think of the literal act of organizing something, like your desk at home or work, we follow these same strategies. If you have a bunch of papers and mail on the top of your desk, you will likely sort papers into separate piles for separate classes or put bills in a separate place than personal mail. You may have one drawer for pens, pencils, and other supplies and another drawer for files. In this case, you are grouping items based on similarities and differences. You may also group things based on proximity, for example, by putting financial items like your checkbook, a calculator, and your pay stubs in one area so you can update your budget efficiently. In summary, we simplify information and look for patterns to help us more efficiently communicate and get through life.

Interpreting Information

Although selecting and organizing incoming stimuli happens very quickly, and sometimes without much conscious thought, interpretation can be a much more deliberate and conscious step in the perception process (Vannuscorps & Caramazza, 2016). Interpretation is the third part of the perception process, in which we assign meaning to our experiences using mental structures known as schemata. Schemata are like databases of stored, related information that we use to interpret new experiences. We all have fairly complicated schemata that have developed over time as small units of information combine to make information that is more complex.

We have an overall schema about how to interpret experiences with teachers and classmates. This schema started developing before we even went to preschool based on things that parents, peers, and the media told us about school. For example, you learned that certain symbols and objects like an apple, a ruler, a calculator, and a notebook are associated with being a student or teacher. You learned new concepts like grades and recess, and you engaged in new practices like doing homework, studying, and taking tests. You also formed new relationships with teachers, administrators, and classmates. As you progressed through your education, your schema adapted to the changing environment. How smooth or troubling schema reevaluation and revision is varies from situation to situation and person to person. For example, some students, when faced with new expectations for behavior and academic engagement, adapt their schema relatively easily as they move from elementary, to middle, to high school, and on to college. Other students do not adapt as easily and holding onto their old schema creates problems as they try to interpret new information through old, incompatible schema.

It is important to be aware of schemata because our interpretations affect our behavior (Rumelhart, 2017). For example, if you are doing a group project for class and you perceive a group member to be shy based on your schema of how shy people communicate, you may avoid giving him presentation responsibilities in your group project because you do not think shy people make good public speakers. Schemata also guide our interactions, providing a script for our behaviors. We know, in general, how to act and communicate in a waiting room, in a classroom, on a first date, and on a game show. Even a person who has never been on a game show can develop a schema for how to act in that environment by watching The Price Is Right, for example. People go to great lengths to make shirts with clever sayings or act enthusiastically in hopes of being picked to be a part of the studio audience and become a contestant on the show.

2.2 Perceiving Others

Are you a good judge of character? How quickly can you “size someone up?” Interestingly, research shows that many people are surprisingly accurate at predicting how an interaction with someone will unfold based on initial impressions. Researchers investigated the ability of people to make a judgment about a person’s competence after as little as 100 milliseconds of exposure to politicians’ faces. Even more surprising is that people’s judgments of competence, after exposure to two candidates for senate elections, accurately predicted election outcomes (Ballew II & Todorov, 2007). In short, after only minimal exposure to a candidate’s facial expressions, people made judgments about the person’s competence, and those candidates judged more competent were people who actually won elections! As you read this section, keep in mind that these principles apply to how you perceive others and to how others perceive you. Just as others make impressions on us, we make impressions on others.

Attribution and Interpretation

You probably have a family member, friend, or coworker with whom you have ideological or political differences. When conversations and inevitable disagreements occur, you may view this person as “pushing your buttons” if you are invested in the issue being debated, or you may view the person as “on their soapbox” if you are not invested. In either case, your existing perceptions of the other person were probably reinforced after your conversation. You may leave the conversation thinking, “She is never going to wake up and see how ignorant she is! I don’t know why I even bother trying to talk to her!” Similar situations occur regularly. Some key psychological processes play into how we perceive others’ behaviors. By examining these processes, attribution in particular, we can see how our communication with others is affected by the explanations we create for others’ behavior. In addition, we will learn some common errors that we make in the attribution process that regularly lead to conflict and misunderstanding.

Attribution

In most interactions, we are constantly running an attribution script in our minds, which essentially tries to come up with explanations for what is happening (Crittenden, 1983). Why did my neighbor slam the door when she saw me walking down the hall? Why is my partner being extra nice to me today? Why did my officemate miss our project team meeting this morning? In general, we seek to attribute the cause of others’ behaviors to internal or external factors. Internal attributions connect the cause of behaviors to personal aspects such as personality traits. External attributions connect the cause of behaviors to situational factors. Attributions are important to consider because the explanations we reach are influenced by the behaviors of other people (Crittenden, 1983). Imagine that Gloria and Jerry are dating. One day, Jerry gets frustrated and raises his voice to Gloria. She may find that behavior more offensive and even consider breaking up with him if she attributes the cause of the blow up to his personality, since personality traits are usually fairly stable and difficult to control or change.

Conversely, Gloria may be more forgiving if she attributes the cause of his behavior to situational factors beyond Jerry’s control, since external factors are usually temporary. If she makes an internal attribution, Gloria may think, “Wow, this person is really a loose cannon. Who knows when he will lose it again?” If she makes an external attribution, she may think, “Jerry has been under a lot of pressure to meet deadlines at work and hasn’t been getting much sleep. Once this project is over, I’m sure he’ll be more relaxed.” This process of attribution is ongoing, and, as with many aspects of perception, we are sometimes aware of the attributions we make, and sometimes they are automatic and/or unconscious. Attribution has received much scholarly attention because it is in this part of the perception process that some of the most common perceptual errors or biases occur.

One of the most common perceptual errors is the fundamental attribution error, which refers to our tendency to explain others’ behaviors using internal rather than external attributions (Sillars, 1980). If you Google some clips from the reality television show Parking Wars, you will see the ire that people often direct at parking enforcement officers. In this case, illegally parked students attribute the cause of their situation to the malevolence of the parking officer, essentially saying they got a ticket because the officer was a mean/bad person, which is an internal attribution. Students were much less likely to acknowledge that the officer was just doing his or her job (an external attribution) and the ticket was a result of the student’s decision to park illegally.

Perceptual errors can also be biased, and in the case of the self-serving bias, the error works out in our favor (Shepperd, Malone, & Sweeny, 2008). Just as we tend to attribute others’ behaviors to internal rather than external causes, we do the same for ourselves, especially when our behaviors have led to something successful or positive. When our behaviors lead to failure or something negative, we tend to attribute the cause to external factors. Thus, the self-serving bias is a perceptual error through which we attribute the cause of our successes to internal personal factors while attributing our failures to external factors beyond our control (Shepperd, Malone, & Sweeney, 2008). When we look at the fundamental attribution error and the self-serving bias together, we can see that we are likely to judge ourselves more favorably than another person, or at least less personally.

Physical and Environmental Influences on Perception

We make first impressions based on a variety of factors, including physical and environmental characteristics. In terms of physical characteristics, style of dress and grooming are important, especially in professional contexts. We have general schema regarding how to dress and groom for various situations ranging from formal, to business casual, to casual, to lounging around the house.

You would likely be able to offer some descriptors of how a person would look and act from the following categories: a Goth person, a preppie, a jock, a fashionista, a hipster. We form the schema associated with these various cliques or styles through personal experience and exposure to media representations of these groups. Different professions also have schema for appearance and dress. Imagine a doctor, mechanic, congressperson, exotic dancer, or mail carrier. Each group has clothing and personal styles that create and fit into general patterns. Of course, the mental picture we have of any of the examples above is not going to be representative of the whole group, meaning that stereotypical thinking often exists within our schema.

Culture, Personality, and Perception

Our cultural identities and our personalities affect our perceptions. Sometimes we are conscious of the effects and sometimes we are not. In either case, we have a tendency to favor others who exhibit cultural or personality traits that match up with our own. This tendency is so strong that is often leads us to assume that people we like are more similar to us than they actually are. Knowing more about how these forces influence our perceptions can help us become more aware of and competent in regards to the impressions we form of others.

Culture

Race, gender, sexual orientation, class, ability, nationality, and age all affect the perceptions that we make. Our cultural identities influence the schemata through which we interpret what we perceive (Schwartz, 2020). As we become socialized into various cultural identities, we internalize beliefs, attitudes, and values shared by others in our cultural group. Schemata held by members of a cultural identity group have similarities, but schemata held by different cultural groups may vary greatly. Until we learn how other cultural groups perceive their world, we will likely have a narrow or naïve view of the world and assume that others see things the way we do. Exposing yourself to and experiencing cultural differences in perspective does not mean that you have to change your schema to match another cultural group’s schema. Instead, it may offer you a chance to understand better why and how your schemata were constructed the way they were.

As we have learned, perception starts with information that comes in through our senses (Macpherson, 2011). Our culture influences how we perceive even basic sensory information. The following list illustrates this:

- Sight. People in different cultures “read” art in different ways, differing in terms of where they start to look at an image and the types of information they perceive and process.

- Sound. “Atonal” music in some Asian cultures is unpleasing; it is uncomfortable to people who are not taught that these combinations of sounds are pleasing.

- Touch. In some cultures, it would be very offensive for a man to touch—even tap on the shoulder—a woman who is not a relative.

- Taste. Tastes for foods vary greatly around the world. “Stinky tofu,” which is a favorite snack of people in Taipei, Taiwan’s famous night market, would likely be very off-putting in terms of taste and smell to many foreign tourists.

- Smell. While Americans spend considerable effort to mask natural body odor (which we typically find unpleasant) with soaps, sprays, and lotions, some other cultures would not find unpleasant or even notice what we consider “b.o.” Those same cultures may find an American’s “clean” (soapy, perfumed, deodorized) smell unpleasant.

Personality

Potential employers often conduct “employment verifications” during which they ask general questions about the applicant. While they may ask a few questions about intellectual ability or academic performance, they typically ask questions that try to create a personality profile of the applicant. They want to know what kind of leader, coworker, and person he or she is. This is a smart move on their part, because our personalities greatly influence how we see ourselves in the world and how we perceive and interact with others.

Personality refers to a person’s general way of thinking, feeling, and behaving based on underlying motivations and impulses (McCornack, 2007). These underlying motivations and impulses form our personality traits. Personality traits are “underlying,” but they are fairly enduring once a person reaches adulthood. That is not to say that people’s personalities do not change, but major changes in personality are not common unless they result from some form of trauma. Although personality scholars believe there are thousands of personalities, they all comprise some combination of the same few traits. Much research has been done on personality traits, and the “Big Five” that are most commonly discussed are extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness (McCrea, 2001). These five traits appear to be representative of personalities across cultures.

The Big Five Personality Traits

- Extraversion. Refers to a person’s interest in interacting with others. People with high extraversion are sociable and often called “extroverts.” People with low extraversion, often called “introverts,” are less sociable.

- Agreeableness. Refers to a person’s level of trustworthiness and friendliness. People with high agreeableness are cooperative and likable. People with low agreeableness are suspicious of others and sometimes aggressive. This makes it more difficult for people to find them pleasant to be with.

- Conscientiousness. Refers to a person’s level of self-organization and motivation. People with high conscientiousness are methodical, motivated, and dependable. People with low conscientiousness are less focused, careful, and dependable.

- Neuroticism. Refers to a person’s level of negative thoughts regarding himself or herself. People high in neuroticism are insecure, experience emotional distress, and may be perceived as unstable. People low in neuroticism are more relaxed, have less emotional swings, and are perceived as more stable.

- Openness. Refers to a person’s willingness to consider new ideas and perspectives. People high in openness are creative and are perceived as open minded. People low in openness are more rigid, set in their thinking, and are perceived as “set in their ways.”

2.3 Perceiving and Presenting Self

Just as our perception of others affects how we communicate, so does our perception of ourselves. But what influences our self-perception? How much of our self is a product of our own making? How much of it is constructed based on how others react to us? How do we present ourselves to others in ways that maintain our sense of self or challenge how others see us? We will begin to answer these questions in this section as we explore self-concept, self-esteem, and self-presentation.

Self-Concept

Self-concept refers to the overall idea of who a person thinks he or she is (Markus, Smith, & Moreland, 1985). If I said, “Tell me who you are,” your answers would be clues as to how you see yourself, your self-concept. Each person has an overall self-concept that might be encapsulated in a short list of overarching characteristics that he or she finds important. However, each person’s self-concept is also influenced by context, meaning we think differently about ourselves depending on the situation. In some situations, personal characteristics, such as our abilities, personality, and other distinguishing features, will best describe who we are. You might consider yourself laid back, traditional, funny, open minded, or driven, or you might label yourself a leader or a thrill seeker. In other situations, our self-concept may be tied to group or cultural membership. For example, you might consider yourself a member of the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity, a Southerner, or a member of the track team.

We also form our self-concept through our interactions with others and their reactions to us. The concept of the looking glass self explains that we see ourselves reflected in other people’s reactions to us and then form our self-concept based on how we believe other people see us (Cooley, 1902; Yeung & Martin, 2003). This reflective process of building our self-concept is based on what other people have actually said, such as “You’re a good listener,” and other people’s actions, such as coming to you for advice. These thoughts evoke emotional responses that feed into our self-concept. For example, you may think, “I’m glad that people can count on me to listen to their problems.”

We also develop our self-concept through comparisons to other people. Social comparison theory states that we describe and evaluate ourselves in terms of how we compare to other people. Social comparisons are based on two dimensions: superiority/inferiority and similarity/difference (Hargie, 2011). In terms of superiority and inferiority, we evaluate characteristics like attractiveness, intelligence, athletic ability, and so on. For example, you may judge yourself more intelligent than your brother or less athletic than your best friend, and these judgments are incorporated into your self-concept. This process of comparison and evaluation is not necessarily a bad thing, but it can have negative consequences if our reference group is not appropriate. Reference groups are the groups we use for social comparison, and they typically change based on what we are evaluating. In terms of athletic ability, many people choose unreasonable reference groups with which to engage in social comparison. If a man wants to get into better shape and starts an exercise routine, he may be discouraged by his difficulty keeping up with the aerobics instructor or running partner and judge himself as inferior, which could negatively affect his self-concept. Using as a reference group people who have only recently started a fitness program but have shown progress could help maintain a more accurate and hopefully positive self-concept.

We also engage in social comparison based on similarity and difference. Since self-concept is context specific, similarity may be desirable in some situations and difference more desirable in others. Factors like age and personality may influence whether or not we want to fit in or stand out. Although we compare ourselves to others throughout our lives, adolescent and teen years usually bring new pressure to be similar to or different from particular reference groups. Think of all the cliques in high school. Think about how people voluntarily and involuntarily broke off into groups based on popularity, interest, culture, or grade level. Some kids in your high school probably wanted to fit in with and be similar to other people in the marching band but be different from the football players. Conversely, athletes were probably more apt to compare themselves, in terms of similar athletic ability, to other athletes rather than kids in show choir. Nevertheless, social comparison can be complicated by perceptual influences. As we learned earlier, we organize information based on similarity and difference, but these patterns do not always hold true. Even though students involved in athletics and students involved in arts may seem very different, a dancer or singer may also be very athletic, perhaps even more so than a member of the football team. As with other aspects of perception, there are positive and negative consequences of social comparison.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the judgments and evaluations we make about our self-concept. While self-concept is a broad description of the self, self-esteem is a more specifically an evaluation of the self (Byrne, 1996). If I again prompted you to “Tell me who you are,” and then asked you to evaluate (label as good/bad, positive/negative, desirable/undesirable) each of the things you listed about yourself, I would get clues about your self-esteem. Like self-concept, self-esteem has general and specific elements. Generally, some people are more likely to evaluate themselves positively while others are more likely to evaluate themselves negatively (Brockner, 1988). More specifically, our self-esteem varies across our life span and across contexts.

2.4 Improving Perception

So far, we have learned about the perception process and how we perceive others and ourselves. Now we will turn to a discussion of how to improve our perception. Our self-perception can be improved by becoming aware of how schema, socializing forces, self-fulfilling prophecies, and negative patterns of thinking can distort our ability to describe and evaluate ourselves. How we perceive others can be improved by developing better listening and empathetic skills, becoming aware of stereotypes and prejudice, developing self-awareness through self-reflection, and engaging in perception checking.

Improving Self-Perception

Our self-perceptions can and do change (Bem, 1972). Recall that we have an overall self-concept and self-esteem that are relatively stable. We also have context-specific self-perceptions. Context-specific self-perceptions vary depending on the person with whom we are interacting, our emotional state, and the subject matter being discussed. Becoming aware of the process of self-perception and the various components of our self-concept will help you understand and improve your self-perceptions.

Since self-concept and self-esteem are so subjective and personal, it would be inaccurate to say that someone’s self-concept is “right” or “wrong.” Instead, we can identify negative and positive aspects of self-perceptions as well as discuss common barriers to forming accurate and positive self-perceptions. We can also identify common patterns that people experience that interfere with their ability to monitor, understand, and change their self-perceptions. Changing your overall self-concept or self-esteem is not an easy task given that these are overall reflections on who we are and how we judge ourselves that are constructed over many interactions. A variety of life-changing events can quickly alter our self-perceptions. Think of how your view of yourself changed when you moved from high school to college. Similarly, other people’s self-perceptions likely change when they enter into a committed relationship, have a child, make a geographic move, or start a new job.

Let’s now discuss some suggestions to help avoid common barriers to accurate and positive self-perceptions and patterns of behavior that perpetuate negative self-perception cycles.

Avoid Reliance on Rigid Schema

As we learned earlier, schemata are sets of information based on cognitive and experiential knowledge that guide our interaction. We rely on schemata almost constantly to help us make sense of the world around us. Sometimes schemata become so familiar that we use them as scripts, which prompts mindless communication and can lead us to overlook new information that may need to be incorporated into the schema. Therefore, it is important to remain mindful of new or contradictory information that may warrant revision of a schema. Being mindful is difficult, however, especially since we often unconsciously rely on schemata. Think about how when you are driving a familiar route you sometimes fall under “highway hypnosis.” Despite all the advanced psychomotor skills needed to drive, such as braking, turning, and adjusting to other drivers, we can pull into a familiar driveway or parking lot having driven the whole way on autopilot. Again, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Have you slipped into autopilot on a familiar route only to remember that you are actually going somewhere else after you have already missed your turn? This example illustrates the importance of keeping our schemata flexible and avoiding mindless communication.

Beware of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

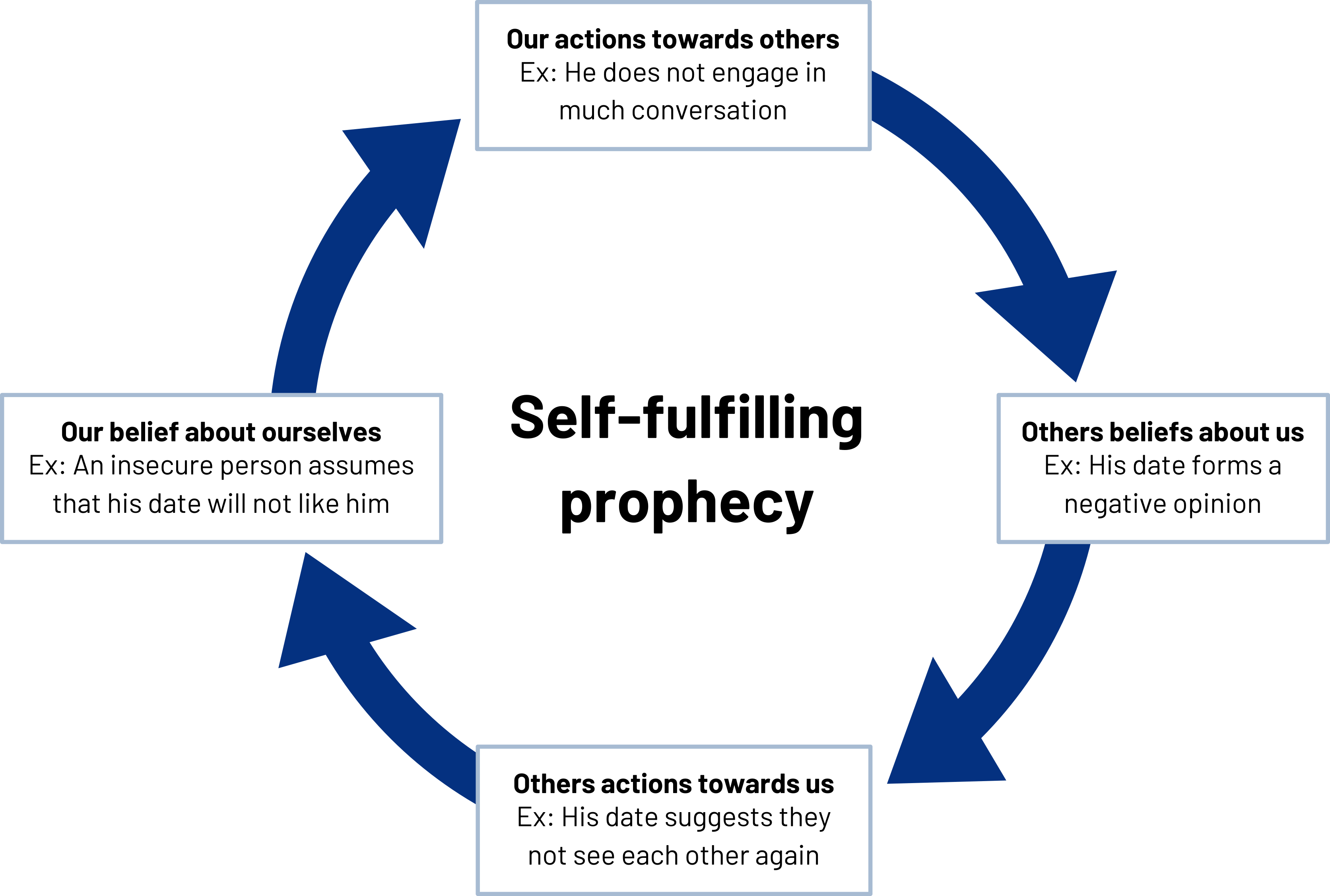

Self-fulfilling prophecies are thought and action patterns in which a person’s false belief triggers a behavior that makes the initial false belief actually or seemingly come true (Guyll et al., 2010). For example, let’s say a student’s biology lab instructor is a Chinese person who speaks English as a second language. The student falsely believes that the instructor will not be a good teacher because he speaks English with an accent. Because of this belief, the student does not attend class regularly and does not listen actively when she does attend. Because of these behaviors, the student fails the biology lab, which then reinforces her original belief that the instructor was not a good teacher.

Although the concept of self-fulfilling prophecies was to be applied to social inequality and discrimination, it has since been applied in many other contexts, including interpersonal communication.

This research has found that some people are chronically insecure, meaning they are very concerned about being accepted by others but constantly feel that other people will dislike them. This can manifest in relational insecurity, which is based on feelings of inferiority resulting from social comparison with others perceived to be more secure and superior. Such people often end up reinforcing their belief that others will dislike them because of the behaviors triggered by their irrational belief.

Take the following scenario as an example: An insecure person assumes that his date will not like him. During the date, he does not engage in much conversation, discloses negative information about himself, and exhibits anxious behaviors. Because of these behaviors, his date forms a negative impression and suggests they not see each other again, reinforcing his original belief that the date would not like him. The example shows how a pattern of thinking can lead to a pattern of behavior that reinforces the thinking, and so on. Luckily, experimental research shows that self-affirmation techniques can be used successfully to intervene in such self-fulfilling prophecies. Thinking positive thoughts and focusing on personality strengths can stop this negative cycle of thinking. It has also been shown to have positive effects on academic performance, weight loss, and interpersonal relationships (Stinson, Logel, Shepherd, & Zanna, 2011).

Overcoming Barriers to Perceiving Others

Many barriers prevent us from competently perceiving others. While some are more difficult to overcome than others are, they can all be addressed by raising our awareness of the influences around us and committing to monitoring, reflecting on, and changing some of our communication habits. Various filters and blinders (lazy listening skills, lack of empathy, or stereotypes and prejudice) influence how we perceive and respond to others.

Beware of Stereotypes and Prejudice

Stereotypes are sets of beliefs that we develop about groups, which we then apply to individuals from that group. Stereotypes are schemata that are taken too far, as they reduce and ignore a person’s individuality and the diversity present within a larger group of people. Stereotypes can be based on cultural identities, physical appearance, behavior, speech, beliefs, and values, among other things, and are often caused by a lack of information about the target person or group (Guyll et al., 2010). Stereotypes can be positive, negative, or neutral, but all run the risk of lowering the quality of our communication.

While the negative effects of stereotypes are straightforward in that they devalue people and prevent us from adapting and revising our schemata, positive stereotypes also have negative consequences. For example, the “model minority” stereotype has been applied to some Asian cultures in the United States. Seemingly positive stereotypes of Asian Americans as hardworking, intelligent, and willing to adapt to “mainstream” culture are not always received as positive and can lead some people within these communities to feel objectified, ignored, or overlooked.

Stereotypes can also lead to double standards that point to larger cultural and social inequalities. There are many more words to describe a sexually active female than a male, and the words used for females are disproportionately negative, while those used for males are more positive. Since stereotypes are generally based on a lack of information, we must take it upon ourselves to gain exposure to new kinds of information and people, which will likely require us to get out of our comfort zones. When we do meet people, we should base the impressions we make on describable behavior rather than inferred or secondhand information. When stereotypes negatively influence our overall feelings and attitudes about a person or group, prejudiced thinking results.

Prejudice is negative feelings or attitudes toward people based on their identity or identities (Allport, Clark, & Pettigrew, 1954). Prejudice can have individual or widespread negative effects. At the individual level, a hiring manager may not hire a young man with a physical disability (even though that would be illegal if it were the only reason), which negatively affects that one man. However, if pervasive cultural thinking that people with physical disabilities are mentally deficient leads hiring managers all over the country to make similar decisions, then the prejudice has become a social injustice. In another example, when the disease we know today as AIDS started killing large numbers of people in the early 1980s, response by some health and government officials was influenced by prejudice. Since the disease was primarily affecting gay men, Haitian immigrants, and drug users, the disease was prejudged to be a disease that affected only “deviants” and therefore did not get the same level of attention it would have otherwise. It took many years, investment of much money, and education campaigns to help people realize that HIV and AIDS do not prejudge based on race or sexual orientation and can affect any human.

Engage in Self-Reflection

A good way to improve your perceptions and increase your communication competence in general is to engage in self-reflection. If a communication encounter does not go well and you want to know why, your self-reflection will be much more useful if you are aware of and can recount your thoughts and actions.

Self-reflection can also help us increase our cultural awareness. Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Developing cultural self-awareness often requires us to get out of our comfort zones. Listening to people who are different from us is a key component of developing self-knowledge. This may be uncomfortable, because our taken-for-granted or deeply held beliefs and values may become less certain when we see the multiple perspectives that exist.

We can also become more aware of how our self-concepts influence how we perceive others. We often hold other people to the standards we hold for ourselves or assume that their self-concept should be consistent with our own. For example, if you consider yourself a neat person and think that sloppiness in your personal appearance would show that you are unmotivated, rude, and lazy, then you are likely to think the same of a person you judge to have a sloppy appearance. So asking questions like “Is my impression based on how this person wants to be, or how I think this person should want to be?” can lead to enlightening moments of self-reflection. Asking questions in general about the perceptions you are making is an integral part of perception checking.

Checking Perception

Perception checking is a strategy to help us monitor our reactions to and perceptions about people and communication (Hansen, Resnick, & Galea, 2002). We can use some internal and external strategies. In terms of internal strategies, review the various influences on perception that we have learned about and always be willing to ask yourself, “What is influencing the perceptions I am making right now?” Even being aware of what influences are acting on our perceptions makes us more aware of what is happening in the perception process. In terms of external strategies, we can use other people to help verify our perceptions.

The cautionary adage “Things aren’t always as they appear” is useful when evaluating your own perceptions. Sometimes it is a good idea to bounce your thoughts off someone, especially if the perceptions relate to some high-stakes situation. However, not all situations allow us the chance to verify our perceptions. Preventable crimes have been committed because people who saw something suspicious did not report it even though they had a bad feeling about it. Of course, we have to walk a line between being reactionary and being too cautious, which is difficult to manage. We are ethically and (sometimes) legally required to report someone to the police who is harming himself or herself or others, but sometimes the circumstances are much more uncertain.

References

Figures

Figure 2.1: The perception process. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.2: Women dress in clever t-shirts in hopes of being picked for The Price is Right. Do512. 2012. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/ddHE4M

Figure 2.3: The big 5 personality traits. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.4: Self-fulfilling prophecy example. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0.

Section 2.1

Broadbent, D. E. (2013). Perception and communication. Elsevier.

Coren, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1980). Principles of perceptual organization and spatial distortion: The gestalt illusions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 6(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.6.3.404

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Ma, W. J. (2012). Organizing probabilistic models of perception. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(10), 511-518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.08.010

Rumelhart, D. E. (2017). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition (pp. 33-58). Routledge.

Vannuscorps, G., & Caramazza, A. (2016). Typical action perception without motor simulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(1), 86-91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516978112

Wertz, F. J. (1982). The findings and value of a descriptive approach to everyday perceptual process. Journal of phenomenological psychology, 13(2), 169-195. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916282X00055

Section 2.2

Ballew II, C. C. and Todorov, A. (2007). Predicting political elections from rapid and unreflective face judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(46), 17948-17953. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705435104

Crittenden, K. S. (1983). Sociological aspects of attribution. Annual Review of Sociology, 9(1), 425-446. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.09.080183.002233

Macpherson, F. (2011). Individuating the senses. In F. Macpherson (Ed.), The senses: Classical and contemporary philosophical perspectives (pp. 3-46). Oxford University Press.

McCornack, S. (2007). Reflect & relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

McCrea, R. R. (2002). Trait psychology and culture. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 819-846. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696166

Schwartz, T. (2020). Where is the culture? Personality as the distributive locus of culture. In G. Spindler (Ed.), The making of psychological anthropology (pp. 419-441). University of California Press.

Shepperd, J., Malone, W., & Sweeny, K. (2008). Exploring causes of the self‐serving bias. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 895-908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00078.x

Sillars, A. L. (1980). Attributions and communication in roommate conflicts. Communication Monographs, 47(3), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758009376031

Section 2.3

Byrne, B. M. (1996). Measuring self-concept across the life span: Issues and instrumentation. American Psychological Association.

Brockner, J. (1988). Self-esteem at work: Research, theory, and practice. Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Co.

Cooley, C. (1902). Human nature and the social order. Scribner.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Markus, H., Smith, J., & Moreland, R. L. (1985). Role of the self-concept in the perception of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(6), 1494-1512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.6.1494

Yeung, K. T., & Martin, J. L. (2003). The looking glass self: An empirical test and elaboration. Social Forces, 81(3), 843-879. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0048

Section 2.4

Allport, G. W., Clark, K., & Pettigrew, T. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1-62). Academic Press.

Guyll, M. (2010). The potential roles of self-fulfilling prophecies, stigma consciousness, and stereotype threat in linking Latino/a ethnicity and educational outcomes, Social Issues, 66(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01636.x

Hansen, F. C. B., Resnick, H., & Galea, J. (2002). Better listening: paraphrasing and perception checking–a study of the effectiveness of a multimedia skills training program. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 20(3-4), 317-331. https://doi.org/10.1300/J017v20n03_07

Stinson, D. A., Logel, C., Shepherd, S., & Zanna, M. P. (2011). Rewriting the self-fulfilling prophecy of social rejection: Self-affirmation improves relational security and social behavior up to 2 months later. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1145–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417725

The process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information. The process of perception includes the perception of select stimuli that pass through our perceptual filter

The first part of the perception process, in which we focus our attention on certain incoming sensory information

The second part of the perception process, in which we sort and categorize information that we perceive based on innate and learned cognitive patterns. Three ways we sort things into patterns are by using proximity, similarity, and difference

The third part of the perception process in which we assign meaning to our experiences using mental structures called schemata

Databases of stored, related information that we use to interpret new experiences

This is the perceptual error through which we attribute the causes of our successes to internal personal factors while attributing our failures to external factors beyond our control

The overall idea of who a person thinks they are

We describe and evaluate ourselves in terms of how we compare to other people

The judgments and evaluations we make about our self-concept

Thought and action patterns in which a person’s false belief triggers a behavior that makes the initial false belief actually or seemingly come true

Sets of beliefs that we develop about groups, which we then apply to individuals from that group

Negative feelings or attitudes toward people based on their identity or identities

A strategy to help us monitor our reactions to and perceptions about people and communication